Luhya People and their Culture in Kenya Kenya

Who are the Luhya People in Kenya? The Luhya (also Luyia, Luhia, Abaluhya) are the second largest ethnic group in Kenya, numbering about 5.3 million people. The Luhya are made up of about 16 sub-ethnic groups in Kenya, the most dominant groups being the:

Bukhusu, Maragoli, Wanga, Ava-Nyore (who ruled the Bunyoro Kingdom in present day Uganda), Marama, Idakho, Khisa, Isukha, Tsotso, Tiriki, Khabras, Ava-Nyala, Tachoni, Khayo, Marachi and Samia. One sub-ethnic group is in northern Tanzania and four are in Uganda.

History of the Luhya tribe

The true origin of the Abaluhya is disputable. According to their own oral literature, Luhyas migrated to their present day location from Egypt in the North.

Some historians however believe that the Luhya came from Central and West Africa alongside other Bantus in what is known as the Great Bantu Migration.

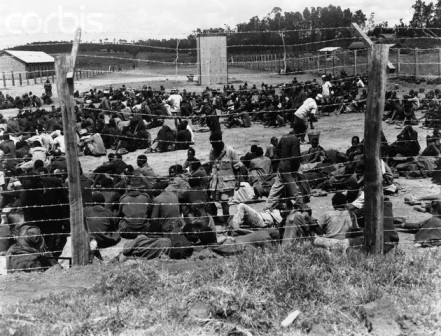

The Luhya tribe, like many other Kenya tribes, lost their most fertile land to the colonialists during the British colonial rule in Kenya.

The Abaluhya, and more so the Bukusu, strongly resisted colonial rule and fought many unsuccessful battles to regain their land. The Wanga and Kabras sub-tribes however collaborated with colonialists.

Luhya People and their Culture in Kenya Kenya

Luhya People and their Culture in Kenya KenyaMigration to their present western Kenya location dates back to as early as the second half of the fifteenth century. Immigrants into present-day Luhyaland came mainly from eastern and western Uganda and trace their ancestry mainly to several Bantu groups, and to other non-Bantu groups such as the Kalenjin, Luo, and Maasai.

Early migration was probably motivated by a search for more and better land, and to escape local conflicts, tsetse flies, and mosquitoes. By about 1850, migration into Luhyaland was largely complete, and only minor internal movements took place after that due to food shortages, disease, and domestic conflicts.

Despite their diverse ethnic ancestry, the Luhya have a history of intermarriage, local trade, and shared social and cultural practices. Variations in dialects and customs reflect their diverse ancestry.

Colonization of Kenya by the British from the 1890s to 1963 forced many communities, including the Luhya, into migrant labor on settler plantations and in urban centers. Because of their large population, the Luhya are considered a powerful political force and have always been active in politics in Kenya

LOCATION OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

Mudavadi, One of the Prominent Politicians from Luhya Tribe

Mudavadi, One of the Prominent Politicians from Luhya Tribe.The Luhya people make their home mainly in the western part of Kenya. Administratively, they occupy mostly Western province, and the west-central part of Rift Valley province. Luhya migration into the Rift Valley is relatively recent, only dating back to the first few years after independence in 1963, when farms formerly occupied by colonial white settlers were bought by, or given back to, indigenous (native) Africans.

According to the last national population census conducted in 1989, the Luhya people number just over 3 million, making up over 10 percent of Kenya's total population.

The Luhya are the second-largest ethnic group in Kenya, after the Kikuyu. Although most Luhya live in western Kenya, especially in the rural areas, an increasingly large number of Luhya have migrated to major urban centers such as Nairobi in search of employment and educational opportunities.

About 900,000 Luhya people live outside of Western province. This is about 30 percent of the total Luhya population.

LANGUAGE OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

LANGUAGE OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

LANGUAGE OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYAThere is no single Luhya language. Rather, there are several mutually understood dialects that are principally Bantu. Perhaps the most identifying linguistic feature of the various Luhya dialects is the use of the prefix aba- or ava-, meaning "of" or "belonging to." Thus, for example, Abalogoli or Avalogoli means "people of logoli ."

Luhya names have specific meanings. Children are named after climatic seasons, and also after their ancestors, often their deceased grandparents or great-grandparents.

Among the Ababukusu, the name Wafula (for a boy) and Nafula (for a girl) would mean "born during heavy rains," while Wekesa (for a boy) and Nekesa (for a girl) would mean "born in the harvest season."

With European contact and the introduction of Christianity at the turn of the twentieth century, Christian and Western European names began to be given as first names, followed by traditional Luhya names. Thus, for example, a boy might be named Joseph Wafula, and a girl, Grace Nekesa.

FOLKLORE OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

One of the most common myths among the Luhya group relates to the origin of the Earth and human beings.

According to this myth, Were (God) first created Heaven, then Earth. The Earth created by Were had three types of soil: top soil, which was black; intermediate soil, which was red; and bottom soil, which was white.

From the black soil, Were created a black man; from the red soil, he created a brown man; and from the white soil, he created a white man.

RELIGION OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

The Luhya people traditionally believed in and worshiped only one god, Were (also known as Nyasaye ).

Were was worshiped through intermediaries (go-betweens), usually the spirits of dead relatives. The spirits had considerable benevolent (positive) as well as malevolent (destructive) power and thus had to be appeased through animal sacrifices, such as goats, chickens, and cattle.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Christianity was introduced to Luhyaland and to the rest of Kenya. Christianity spread widely during the colonial period.

The overwhelming majority of Luhya people now consider themselves Christians. Both Catholicism and Protestantism are practiced. Among the Abawanga, Islam is also practiced.

Despite conversion to Christianity, belief in spirits and witchcraft is still common. It is not unusual to find people offering prayers in church and at the same time consulting witch doctors or medicine men for assistance with problems.

MAJOR HOLIDAYS OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

There are no holidays that are uniquely Luhya. Rather, the Luhya people celebrate the national holidays of Kenya along with the rest of the nation. Among the Abalogoli and Abanyole, an annual cultural festival has recently been initiated, but it is not yet widely adopted. The festival is held on December 31.

RITES OF PASSAGE OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

Having many children is considered a virtue, and childlessness is seen as a great misfortune. Many births take place in the home, but increasingly women are urged to give birth in hospitals or other health facilities.

The placenta (engori) and the umbilical cord (olulera) are buried behind the hut at a secret spot so they will not be found and tampered with by a witch (omulogi). For births that take place in hospitals or other places outside of home, these rituals are not observed.

Until about fifteen years ago, elaborate initiation ceremonies to mark the transition from childhood to adulthood were performed for both boys and girls.

Among other things, these rites included circumcision for boys. Uncircumcised boys (avasinde) were not allowed to marry or join in many other adult activities. Nowadays circumcision still takes place, but the ceremonies are still elaborate and public only among the Ababukusu and Abatiriki peoples.

Death and funeral rites involve not only the bereaved family, but also other relatives and the community.

While it is known that many deaths occur through illnesses like malaria and tuberculosis, as well as road accidents, quite a few deaths are still believed to occur from witchcraft. Burial often takes place in the homestead of the deceased.

Among the Luhya, funerals and burials are public and open events. Animals are slaughtered, and food and drinks are brought to feed the mourners.

Because many people today are Christians, burial ceremonies often involve prayers in church and at the dead person's home, even when traditional rituals are also practiced. Music and dance, both traditional Luhya and Western-style, take place, mostly at night.

RELATIONSHIPS OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

Greetings among the Luhya salute a person, and also involve inquiries about their well-being and that of their families. People take a keen interest in one another's affairs. Shaking hands is a very common form of greeting, and for people who are meeting for the first time in a long while, the handshake will involve not just the clasping of hands, but also a vigorous jerking of the arm.

Shaking hands between a man and his mother-in-law is not allowed among some Luhya communities. Hugging is not common. Women may hug each other, but crossgender hugging is rare.

Women are expected to defer to men, especially to their husbands, fathers-in-law, and the older brothers of their husband. Thus, in a conversation with any of these men, women will tend (or are expected) to lower their heads, fold their hands, and look down.

Visits are very common among the Luhya people. Most visits are casual and unannounced. Families strive to provide food for their visitors, especially tea.

Dating among the Luhya is informal and is often not publicly displayed, especially among teenagers. Unless a marriage is seriously intended and planned, a man or a woman may not formally invite their date to their parents' home and introduce him or her.

LIVING CONDITIONS OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

Major health concerns among the Luhya include the prevalence of diseases such as scabies, diarrhea, malaria, malnutrition, and, lately, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

In rural areas, the Luhya live in homesteads with extended families. Houses are mostly made of grass-thatched roofs and mud walls, but an increasing number are made with corrugated iron roofs, and in some cases, walls made of concrete blocks.

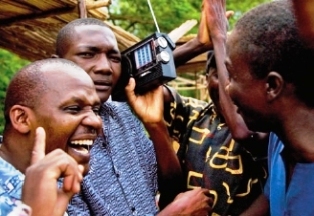

Houses tend to be round or square. Because of the poverty in rural areas, people own very few material goods, and items such as transistor radios and bicycles are highly valued. Cars and televisions are lacking for the most part among the Luhya.

People rely on public transportation (buses and vans), but travel on foot and on bicycles is also very common. Roads in the rural hinterland are not paved and tend to be impassable during heavy rains.

FAMILY LIFE OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

In the rural areas among the Luhya, people live in homesteads or compounds, with each homestead comprising several houses. In one homestead may live an old man (the patriarch, or family head), his married sons and their wives and children, his unmarried sons and daughters, and sometimes other relatives.

Even though each household may run its own affairs, there is a lot of obligatory sharing within the homestead. Families tend to be large, with the average number of children per woman reaching eight.

Women are expected to yield to the wishes of men. Acts of defiance or insubordination by women toward their husbands, fathers-in-law, or other senior male relatives can result in beatings from male relatives, especially one's husband.

Marriage partners must be chosen from outside one's parents' clans or lineages. Polygyny (a man marrying more than one wife) is not widely practiced these days among the Luhya, but it is still fairly common among the Ababukusu subgroup.

Traditionally, a request for marriage is made between the parents of the man and the woman. If the marriage is agreed upon, bride wealth of cattle and cash, called uvukwi among the Avalogoli subgroup, is paid.

Nowadays, however, young people increasingly get married on their own with little input from their parents. Civil and church (Christian) marriages are also becoming common. Bride wealth is still being paid, but amounts differ widely and payment schedules are not strictly honored.

The Luhya keep dogs for security, and cats are kept to manage the mouse population.

CLOTHING OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

Ordinarily, the Luhya dress just like their fellow Kenyans, wearing locally manufactured and imported dresses, pants, shirts, shoes, and so forth. Elementary and high school students wear uniforms to school. Women almost never wear pants.

Those who dare to do so are considered abnormal and may even be verbally assaulted by men. It is particularly inappropriate for a married woman to wear pants or a short skirt or dress in the presence of her father-in-law. Earrings, necklaces, and bangle bracelets are commonly worn by women. Men generally do not wear earrings.

Traditional clothing is worn mostly during specific occasions and only by certain people. In cultural dances, performers may put on feathered hats and skirts made of sisal strands.

For the Luhya groups that still maintain the traditional circumcision rites (especially the Ababukusu), the initiates will often put on clothing made of skins and paint themselves with red ochre (a pigment) or ash.

FOOD OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

Breakfast among the Luhya consists mainly of tea. The preferred tea is made with plenty of milk and sugar.

For those who can afford it, wheat bread bought from the stores is eaten with tea. Tea and bread, however, are too expensive for many families to eat on a regular basis; consequently, porridge made of maize (corn), millet, or finger millet flour is consumed instead.

Lunch and supper often consist of ovukima —maize flour added to boiling water and cooked into a thick paste similar to American grits.

Ovukima is eaten with various vegetables such as kale and collard greens, and for those who can afford it, beef or chicken. Chicken is a delicacy and is prepared for important guests or for special occasions.

The main cooking utensils are pots made of steel or other metals. They are mass-manufactured in the country as well as imported.

Clay pots are also still used by many families for preparing and storing traditional beer, and also for cooking traditional vegetables. Plates and cups are made of either metal, plastic, or china, and are bought from stores, as are spoons, knives, and forks.

EDUCATION AMONG LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

The literacy rate (percentage of the population able to read and write) among the Luhya is close to that of the country as a whole.

The literacy level for the total population of Western province (where the majority of Luhya live) is 67 percent. This is slightly lower than the national average of 69 percent. Literacy among women is slightly lower than among men.

Typically, most people (about 75 percent of the population) drop out of school after primary school education, which (since the mid-1980s) lasts eight years. The main reasons for high drop-out rates are the difficult qualifying examinations to enter high school and expensive school fees.

Parents spend a large portion of their income on their children's education in boarding, uniforms, school supplies, transportation to and from school, and pocket money. Often the family will deny itself many of life's necessities and comforts, such as improved housing, food, and clothing, in order to put children through school.

Consequently, students are expected to finish school and help with the education of younger siblings, as well as to care for their parents in old age. Because very few students are able to attend a university, parents and the community are very proud of those who manage to attain this level of education.

CULTURAL HERITAGE OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

CULTURAL HERITAGE OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

CULTURAL HERITAGE OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYAMusic and dance are an important part of the life of the Luhya. Children sing songs and dance for play and (especially boys) when herding livestock. Occasions such as weddings, funerals, and circumcision ceremonies all call for singing and dancing.

Musical instruments include drums, jingles, flutes, and accordions. The Luhya are nationally renowned for their energetic and vibrant isukuti dance, a celebratory performance involving rapid squatting and rising accompanied by thunderous, rhythmic drumbeats.

EMPLOYMENT

EMPLOYMENT

EMPLOYMENTThe majority of Luhya families are farmers. Because of the high population density (about 2,450 people per square mile, or 900 people per square kilometer) in Luhyaland, most families own only very small pieces of land of less than 1 acre (0.4 hectares), which are very intensively cultivated. Crops include various vegetables such as kale, collard greens, carrots, maize (corn), beans, potatoes, bananas, and cassava. Beverage crops such as tea, coffee, and sugarcane are grown in some parts of Luhyaland.

Livestock, especially cattle and sheep, are also kept. Tending the farm is often a family affair. Because the family farm rarely yields enough food to feed a family and pay for school fees and supplies, clothing, and medical care, family members often seek employment in urban centers and send money back to their rural homes.

Women do most of the domestic chores, such as fetching firewood, cooking, taking care of children, and also the farm work.

SPORTS OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

Numerous games and sports are played by Luhya children. Jumping rope is very popular among girls.

The jumping is counted and sometimes accompanied by rhythmic songs. Hide-and-seek games are common among both boys and girls. Soccer is the most popular game among boys. Any open ground can serve as a playing field.

Adult sports include soccer for men, and to a lesser extent, netball for women. Netball is somewhat like basketball, only the ball is not dribbled. School-based sports also include track-and-field events. The most popular spectator sport is soccer, and some of the best soccer players in Kenya are Luhya.

Luhya people are very enthusiastic about sports especially rugby and soccer. AFC Leopards is one soccer club that enjoys wide support among many Luhyas as it was considered to be their own.

The club was formed in the early 1960s as Abaluhya Football Club, and has traditionally had bitter rivalry with Gor Mahia FC, a club associated with the Luo.

In Kenya’s football history, AFC Leopards and Gor Mahia FC were for a long time the best soccer teams in the country producing most of the players in the national soccer team, the Harambee stars.

Up to this day, traditional bullfighting is viewed as a sport activity among sections of the Luhya ethnic tribe. The annual bullfighting competition attracts many spectators, among them Dr. Bonny Khalwale, the current Member of Parliament (MP) for Ikolomani

RECREATION OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

Battery-operated radios and cassette players provide musical entertainment for many people. Local bars and shops also have radios, cassette players, juke boxes, and other music systems.

Men often gather in these places to drink, play games, and listen and dance to music. Music is mainly of local, Swahili, and Lingala (Congolese) origin, but Western European and American music are also common.

CRAFTS AND HOBBIES OF LUHYA PEOPLE OF KENYA

Pottery and basket-weaving are quite common among the Luhya, especially in the rural areas. Baskets are made from the leaves of date palms (called kamakhendu among the Ababukusu) that grow on river banks. Increasingly, sisal is used.

Body ornaments such as bangle bracelets, necklaces, and earrings are mass-produced commercially in Kenya or are imported, and are not in any way uniquely Luhya in form.

SOCIAL PROBLEMS

Violations of human rights and civil liberties that the Kenya government has been accused of generally apply to most ethnic groups. Problems of alcoholism exist among the Luhya. However, the problems of greatest concern are the high population density and high rate of population growth. Health problems arising from endemic (native) diseases are also of concern

More about Afican Culture

Kenya Culture | Akamba | British Colonialists | Crafts | Cultural Business Meetings | Cultural Communication | Cultural Eye Contact | Cultural Gestures | Gift Giving | Cultural Law | Cultural Music | Cultural Space | Cultural Time | How to Talk in Kenya |Recent Articles

-

Garam Masala Appetizers ,How to Make Garam Masala,Kenya Cuisines

Sep 21, 14 03:38 PM

Garam Masala Appetizers are originally Indian food but of recent, many Kenyans use it. Therefore, on this site, we will guide you on how to make it easily. -

The Details of the Baruuli-Banyara People and their Culture in Uganda

Sep 03, 14 12:32 AM

The Baruuli-Banyala are a people of Central Uganda who generally live near the Nile River-Lake Kyoga basin. -

Guide to Nubi People and their Culture in Kenya and Uganda

Sep 03, 14 12:24 AM

The Nubians consist of seven non-Arab Muslim tribes which originated in the Nubia region, an area between Aswan in southern

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.