Bafumbira People and their Culture in Uganda

Who are the Bafumbira People in Uganda? The Bafumbira are a group of people who make the modern Uganda.

They live in the district of Kisoro in Southwestern Uganda.

They are neighbours to Bakiga, Banyarwanda and Congolese.

Those who inhabit Kisoro District in the extreme southwest of Uganda are called Bafumbira but in actual sense they are Banyarwanda because they practice the same culture.

This is the only district that is inhabited almost exclusively by Banyarwanda.

To their west, is Zaire and to their south is Rwanda. The Bafumbira-Banyarwanda land is mountainous and cool, Bafumbira was part of Rwanda until the boundary adjustments of 1910.

The actual inhabitants of Bafumbira-Banyarwanda, in descending order of numerical superiority, are the Bahuutu, the Batutsi and the Batwa.

Essentially, they are Banyarwanda and they speak Kinyarwanda.

The Batwa are said to have been the original inhabitants of Bufumbira and they are closely related to the Bambuti of Mt. Rwenzori.

The Bahuutu are said to have been the second group to arrive in Bufumbira. Then came the Batutsi before A.D 15o

History of Bafumbira-banyarwanda

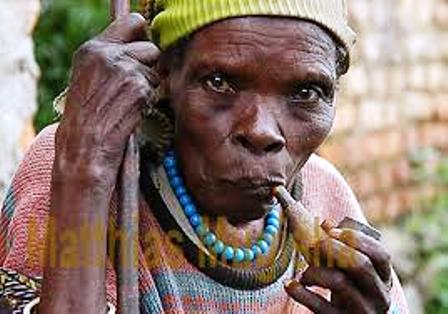

The Batwa do not have traditions of early migration from anywhere. They are believed to have been the earliest inhabitants of East Africa together with the Bambuti of Mt. Rwenzori and Ndorobo of Kenya. To date they do not lead a permanent, settled life.

The Bahuutu are Bantu and, like other Bantu, they are believed to have originated from the Congo region of Central Africa around AD 1000. They are said to have entered Rwanda from northeast.

The Origin of Batutsi is, however, mythical. One theory says that they originated from Karagwe in northern Tanzania.

Another very controversial one is the “Hamitic myth”. This theory has it that the Batutsi are not indigenous to East Africa. And that their original homeland might have been either Somalis or Ethiopia or Egypt. This theory is based, among other things on the fact that the Batutsi tend to resemble the Somali and Galla.

Uncovering Heritage and Traditions Of The Bafumbira

On the hills of Mufumbiro in southwestern Uganda in Kisoro district resides a tribe that has come to be known by some as Rwandese immigrants, and by others as descendants of the Bakiga whose close association with the Rwandese emerged into the Kifumbira, a language 90% similar to Kinyarwanda.

In addition to the almost Kinyarwanda dialect, this confusion is probably brought about by their mixed cultures and tradition, which is a mixture of the Bakiga and Banyarwanda's cultures between whom the Mufumbiro mountains are located.

The physical appearance of Bafumbira is also an additional confusing factor. While some are tall with long facial features associated with the Rwandese Tutsi, others are heavily built and strong. These features could easily get them mistaken for Bakiga or qualify them for the Rwandese Hutu.

The government of Uganda originally considered Bafumbira as Banyarwanda-Bafumbira until the 1995 Uganda Constitution, which recognized Bafumbira as an independent tribe of Ugandans.

Richard Mugisha, a Mufumbira lawyer in Kampala says that the Bafumbira have always resided in Uganda. "Many of the Bafumbira are products of intermarriages between the Bakiga and Rwandese though. These intermarriages and close associations with the two tribes is where most of Bafumbira culture is derived," he explains.

Annet Habyarimanna, another Mufumbira, says that her grandfather was an immigrant from Rwanda whose son married a Mufumbira. "Though my father is a Munyarwanda and my mother a Mufumbira, we consider ourselves as Bafumbira," she explains.

Social Organization

Originally, Bafumbira were divided into clans like the Bagesera and Bungula most with heroic stories attached to them originating from Rwanda.

Like many other African societies, the clans were divided along different totems ranging from animals, plants and birds species. Bafumbira differed from most African socialites however when it came to identifying members of the different clans. Each clan was identified by the hill they occupied.

Like the Banyarwanda and the Bakiga, the Bafumbira do not name their children according to these clans. "Our names do not reflect our clans but rather the circumstances in which one was born," explains Mugisha, whose name means 'a blessing'.

A Sorghum Society

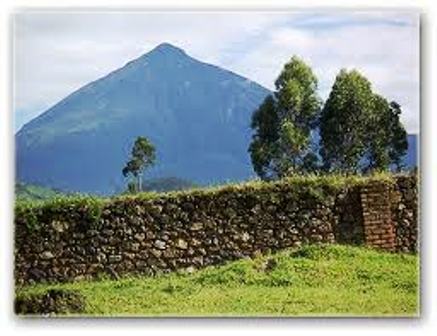

Mufumbiro mountains of Western Rwanda and Southwestern Uganda

Mufumbiro mountains of Western Rwanda and Southwestern UgandaOwing to the rich volcanic soils on the slopes of the Mufumbiro mountains of Western Rwanda and Southwestern Uganda on which they resided, the Bafumbira predominantly became cultivators. Their staple food, even to date, is sorghum that they use dynamically to get different dishes.

Habyarimanna explains that sorghum grains can be cooked if harvested fresh or eaten raw if harvested dry. They can also be ground to make flour from which a variety of drinks is prepared or prepared into omutsima, an equivalent of posho(corn/maize meal) from maize flour.

They also grow potatoes that do well in volcanic soils and legumes, mainly beans. "They tended animals like cows, goats and sheep as well but one rarely came across a family that depended heavily on animal raring," Mugisha explains.

As the population grew, the pressure on the land, which was being repeatedly segmented, rendered the land infertile. This, in addition to land shortage, forced them to move to other areas that offered better soils and enough land for cultivation.

"My parents shifted from Kisoro in search of land and now permanently reside in Ibanda. This is what my children now refer to as their ancestral village," explains Mugisha.

Land shortage alongside growing populations on these mountain slopes has however over the years dealt a significant blow on this social organization. In addition to Bafumbira being scattered among the Bakiga and Banyankole districts, the effects of land shortage have made it almost impossible for the Bafumbira social organization to hold fast today. But some cultural traditions like those on inheritance remain deeply rooted.

Clans and Inheritance Traditions

Unlike most other African traditions, the institution of heirs was not a very restrictive one. Basically, the father chose whom to give his property to in his will. Normally, the first-born son inherited most of the property if he was in good health and was responsible enough to take over the role of being head of a family.

It was not unusual for a parent to pass on his property to his daughters for one reason or another. Apart from the absence of sons, the reason could be because he had enough property to divide amongst all his children or because he thought his daughters deserved the property more than the sons. This however usually did not go down well with the sons who protested that women would get property from their future husbands.

A father was however expected to provide for all his sons to help them start their own families. He thus bequeathed to all his sons in form of land/gardens or animals.

This ensured the maintenance of family heritage, and as an intended result, society cohesiveness among the Bafumbira.

But the Bafumbira clans have almost died out.

"Now that we cannot tell who belongs to what clan depending on the hill on which they reside, the clan divisions have become insignificant," laments Mugisha, adding, "a majority of the young generation therefore do not know anything about these clans let alone have knowledge of their existence."

Also, sons can no longer look up to their parents to hand down land because not all the parents have enough land to divide amongst their children anymore.

There are some traditions however that still hold traces of their ancient cultural practices, at least to a certain extent and among these are those concerning sex and marriage.

Sex, Marriage and Family among the Bafumbira

If you marry among the Bafumbira, all you have to do is impress your in-laws and you will never be required to go back to the field to search for another wife if the need ever arises. In case of death of your wife or barrenness, your in-laws will willingly offer you one of your sisters-in-law to fill the gap.

Maybe this is just as well since the process of getting a wife is long and quite costly. Other than courtship and the bride price, the husband is expected to fight or woo his new bride with gifts to consummate their marriage!

Common to most African cultures, Bafumbira also did not accommodate sexual immorality. It was hard for a Mufumbira girl who conceives outside wedlock to secure a husband and usually her family would send the child to its father's family. Though this will mainly be to minimize the shame that comes with the incident, they usually use the excuse "How can one of a different clan inherit from this clan!

This is a tradition that holds strong in most of the conservative families even today. "It is mainly due to the scarcity of resources too. Parents can not imagine having to divide the little property to include an extra head which is not even entitled to their inheritance," explains Mugisha.

Getting a Spouse

Otherwise, the Bafumbira are among the tribes that took betrothal seriously. Parents could choose a spouse for their child at birth. This sometimes entailed the husband-to-be's family providing resources like a cow to cater for their future daughter in laws welfare.

The other way of finding a spouse is by using a go between who identifies a family suitable enough to provide a bride for the boy/man's family he is representing. The go-between's role would entail identifying a suitable girl and studying her family to eliminate issues like marriage from the same clan.

Contrary to most other societies that used go-betweens to finalize all arrangements for people to wed each other, among the Bafumbira, the man or woman has a say in the choices made for them. This is at a ceremony called Gusaba (asking) where the man's entourage comes to officially declare their intention to the chosen girl's family. After clarifying the known facts with the elders, the young man and woman are asked whether they approve of the decisions made by parents and go-betweens.

The girl's family also got a chance to examine the boy's family's property and decided on what they wanted for bride price if they approve. This provided an opportunity for them to check out the family to which they are sending their daughter.

Bride Price and Bridal Preparation

At another ceremony, the Gukwa, the groom brings the bride price and discussions are held to decide on the date for Gushingira, the equivalent of Kuhingira among the Bakiga and Banyankole, or Kwanjula among the Baganda.

Between the Gukwa and Gushingira, which is the day the groom takes his bride, her family takes extra care of the bride to be. She is kept indoors for about a month and prohibited from taking part in the household chores. In addition, she is fed on milk and gee which is also smeared allover her body every day. This is also done by the Banyarwanda and is meant to give away a bride at her best, with regards to health and appearance. It is called Kwalika.

During this time also, the mother takes her daughter through what is expected of her as a bride and eventually as a wife. Among these is the fact that she should not let her virginity go easily or it will imply she is cheap.

It was, as it is today, amidst tears at the bride's home that the bride is finally sent away with the messengers from the groom when the day for the Gushingira finally comes.

The bride, looking her best, cries because she is leaving her mother and is not sure what lies ahead. The pensive mother to the bride tries to encourage her daughter to go and make a new life for herself. It is only the males at the girl's home who are openly happy about the bride's departure.

It is at her in-laws', where she is received amidst celebration that the real wedding ceremony happens. Although the bride is in a pensive mood, there is a lot of food, dancing and jubilation all day long.

At the Bride's New Home

The wedding night is usually a tough one for the new couple. The bride fights to retain her virginity, assisted with under wear specially worn for that night. Her under wear is secured with strings that make it hard to peel off her body. If the husband fails to persuade her or use force, he tries to woo her with gifts to remove the unusual underwear for them to engage in conjugal activities as man and wife.

At her new home, the bride is again kept inside the house for sometime being given special treatment. This is called Kwalula. It is in preparation for the time her aunt, friends and other family members are invited to come and check on how she is faring in the new family.

During this time, the bride will do all her work in doors. Since it is assumed that the bachelor did not have any household equipment of his own, his bride will use her mother-in-law's utensils in the meantime. Although she shares a house with her husband, all this time, officially she does not yet have a home of her own. When the entourage from her family approve of her welfare, they officially bring her out of the house. This is another day of celebration.

The new couple is then entitled to a new home and can operate independently of the man's family. This period tested how well the bride will relate with her in-laws especially her mother-in-law, which is determined by the duration of the Kwalula. If they were fond of each other, the in-laws would not want to let the bride go independent so it took a longer time that could even be three months.

On the other hand, it could take less than a month if the bride and her in-laws could not stand one another. This could however also follow a request by the new couple to go independent as quickly as possible. This decision was mostly arrived at with the advice and help of the aunt (Ssenga).

The Aunt/Ssenga

The Aunt/Ssenga

The Aunt/SsengaAlthough the girl's paternal aunt is recognized like in most African cultures, her main role among the Bafumbira is after the marriage has started. She is the only person who can be told the innermost secrets of the couple's household. The bride is for instance not supposed to give away her virginity willingly even after marriage.

If the groom thus fails to consummate the marriage forcefully or with gifts, he asks the aunt to convince her niece.

She will be present at the births of at least her niece's first child to guide her. The aunt is also the linkage between the two families that have been brought together by the marriage. She is the one through whom a groom will be offered a new bride in case he is dissatisfied with his wife or she dies.

Polygamy and Death of A Spouse

Polygamy and Death of A Spouse

Polygamy and Death of A SpouseWhile a man was allowed to remarry in case his wife died, it was not the same with the women. In case of death of a husband, a woman is not expected to remarry but rather take care of her husband's property and children. It is an honor in Kifumbira society for a widow to successfully bring up her children without being remarried.

Polygamy was only allowed among the wealthy that could afford to take care of more than one wife. A man was also allowed to marry from the same family if it was well with him and his in-laws.

Of course most of these traditions have been eroded by modernity and a new world economic order that has seen it impossible to go forward with some cultural practices.

More about Afican Culture

Kenya Art | Kenya Festivals | Kenya Gender Issues | Kenya Gestures | Kenya Greetings | Kenya History | Kenya Language | Kenya Literature | Kenya Modern Culture | Kenya Music | Kenya National Anthem | National Dress Cord of Kenya | Kenya People | Kenya Respect | Kenya Taboos | Kenya Television and Culture |

Recent Articles

-

Garam Masala Appetizers ,How to Make Garam Masala,Kenya Cuisines

Sep 21, 14 03:38 PM

Garam Masala Appetizers are originally Indian food but of recent, many Kenyans use it. Therefore, on this site, we will guide you on how to make it easily. -

The Details of the Baruuli-Banyara People and their Culture in Uganda

Sep 03, 14 12:32 AM

The Baruuli-Banyala are a people of Central Uganda who generally live near the Nile River-Lake Kyoga basin. -

Guide to Nubi People and their Culture in Kenya and Uganda

Sep 03, 14 12:24 AM

The Nubians consist of seven non-Arab Muslim tribes which originated in the Nubia region, an area between Aswan in southern

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.