Banyankole People and their Culture in Uganda

Who are the Banyankole People in Uganda? Ankole, also referred to as Nkore, is one of four traditional kingdoms in Uganda. The kingdom is located in the southwestern Uganda, east of Lake Edward. It was ruled by a monarch known as The Mugabe or Omugabe of Ankole. The kingdom was formally abolished in 1967 by the government of President Milton Obote, and is still not officially restored.

The people of Ankole are called Banyankole (singular: Munyankole) in Runyankole language, a Bantu language.

On October 25, 1901, the Kingdom of Nkore was incorporated into the British Protectorate of Uganda by the signing of the Ankole agreement.

Due to the reorganisation of the country by Idi Amin, Ankole no longer exists as an administrative unit. It is divided into six districts: Bushenyi District, Ntungamo District,Mbarara District, Kiruhura District, Ibanda District and Isingiro District.

This former kingdom is well known for its long-horned cattle, which were objects of economic significance as well as prestige. The Mugabe (King) was an absolute ruler. He claimed all the cattle throughout the country as his own.

Chiefs were ranked not by the land that they owned but by the number of cattle that they possessed. Banyankole society is divided into a high-ranked caste (social class) of pastoralists (nomadic herders) and a lower-ranked caste of farmers.

The Bahima are cattle herders and the Bairu are farmers who also care for goats and sheep.

In 1967, the government of Milton Obote, prime minister of Uganda, abolished kingdoms in Uganda, including the Kingdom of Ankole.

This policy was intended to promote individualism and socialism in opposition to traditional social classes. Nevertheless, cattle are still highly valued among the Banyankole, and the Bahima are still held in high regard.

History of pre-colonial ethnic relations in Ankole

The pastoralist Hima (also known as Bahima) established dominion over the agricultural iru (also known as Bairu) some time before the nineteenth century.

The Hima and Iru established close relations based on trade and symbolic recognition, but they were unequal partners in these relations. The Iru were legally and socially inferior to the Hima, and the symbol of this inequality was cattle, which only the Hima could own.

The two groups retained their separate identities through rules prohibiting intermarriage and, when such marriages occurred, making them invalid.

The Hima provided cattle products that otherwise would not have been available to Iru farmers. Because the Hima population was much smaller than the Iru population, gifts and tribute demanded by the Hima could be supplied fairly easily.

These factors probably made Hima-Iru relations tolerable, but they were nonetheless reinforced by the superior military organization and training of the Hima.

The kingdom of Ankole expanded by annexing territory to the south and east. In many cases, conquered herders were incorporated into the dominant Hima stratum of society, and agricultural populations were adopted as Iru or slaves and treated as legal inferiors. Neither group could own cattle, and slaves could not herd cattle owned by the Hima.

Royal Regalia Kingship

Royal Regalia KingshipAnkole society evolved into a system of ranked statuses, where even among the cattle-owning elite, patron-client ties were important in maintaining social order.

Men gave cattle to the king (mugabe) to demonstrate their loyalty and to mark life-cycle changes or victories in cattle raiding.

This loyalty was often tested by the king's demands for cattle or for military service. In return for homage and military service, a man received protection from the king, both from external enemies and from factional disputes with other cattle owners.

The mugabe authorized his most powerful chiefs to recruit and lead armies on his behalf, and these warrior bands were charged with protecting Ankole borders.

Only Hima men could serve in the army, however, and the prohibition on Iru military training almost eliminated the threat of Iru rebellion. Iru legal inferiority was also symbolized in the legal prohibition against Iru owning cattle.

And, because marriages were legitimized through the exchange of cattle, this prohibition helped reinforce the ban on Hima-Iru intermarriage.

The Iru were also denied highlevel political appointments, although they were often appointed to assist local administrators in Iru villages.

The Iru had a number of ways to redress grievances against Hima overlords, despite their legal inferiority. Iru men could petition the king to end unfair treatment by a Hima patron. Iru people could not be subjugated to Hima cattle-owners without entering into a patron-client contract.

A number of social pressures worked to destroy Hima domination of Ankole. Miscegenation took place despite prohibitions on intermarriage, and children of these unions (abambari) often demanded their rights as cattle owners, leading to feuding and cattle-raiding.

From what is present-day Rwanda groups launched repeated attacks against the Hima during the nineteenth century.

To counteract these pressures, several Hima warlords recruited Iru men into their armies to protect the southern borders of Ankole.

LOCATION OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

Ankole lies to the southwest of Lake Victoria in southwestern Uganda. Sometime during or before the seventeenth century, cattle-keeping people migrated from the north into central and western Uganda and mingled with indigenous farming peoples.

They adopted the language of the farmers but maintained their separate identity and authority, most notably in the Kingdom of Ankole.

The country was well suited for pastoralism (nomadic herding). Its rolling plains were covered with abundant grass. Today, ideal grazing land is diminishing due to a high rate of population growth.

LANGUAGE OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

The Banyankole speak a Bantu language called Runyankole. It is a member of the Niger-Kordofanian group of language families. In many of these languages, nouns are composed of modifiers known as prefixes, infixes, and suffixes.

Word stems alone have no grammatical meaning. For example, the prefix ba -signifies plurality; thus, the ethnic group carries the name Ba nyankole.

An individual person is a Mu nyankole, with the prefix mu -carrying the idea of singularity. Things pertaining to or belonging to the Banyankole are referred to as Ki nyankole, taking the prefix ki -.

The pastoral Banyankole are known as Ba hima; an individual of this group is referred to as a Mu hima. The agricultural Banyankole are known as Ba iru; the individual is a Mu iru.

FOLKLORE OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

Legends and tales teach proper moral behavior to the young. Storytelling is a common means of entertainment. Both men and women excel in this verbal art form.

Riddles and proverbs are also emphasized. Of special significance are legends surrounding the institution of the kingship, which provide a historical framework for the Banyankole.

Folktales draw on themes such as royalty, cattle, hunting, and other central concerns of the Banyankole. Animals figure prominently in the tales.

One well-known tale concerns the Hare and the Leopard. The Hare and the Leopard were once great friends.

When the Hare went to his garden for farming, he rubbed his legs with soil and then went home without doing any work, even though he told Leopard that he was always tired from digging.

Hare also stole beans from Leopard's plot and said that they were his own. Eventually, Leopard realized that his crops were being stolen, and he set a trap in which Hare was caught in the act of stealing.

While stuck in the trap, Hare called to Fox, who came and set him free. Conniving Hare told Fox to put his own leg into the trap to see how it functioned.

Hare then called Leopard, who came and killed Fox, the assumed thief, without asking any questions.

The Banyankole recite this story to illustrate that one should not trust easily, as Leopard trusted Hare. One should also not act too quickly, as Leopard did in killing the innocent Fox.

RELIGION OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

The majority of Banyankole today are Christians. They belong to major world denominations, including the Roman Catholic Church, or the Church of Uganda, which is Anglican.

Fundamental Christianity, such as Evangelicalism, is also common. Public confessions of such sins as adultery and drunkenness are common, as well as rejection of many traditional secular and religious practices.

The element of indigenous Kinyankole religion that survives most directly today is the belief in ancestor spirits. It is still believed that many illnesses result from neglect of a dead relative, especially a paternal relative.

Through divination it is determined which ancestor has been neglected. Presents of meat or milk and/or changes in behavior can appease the ancestor's spirit.

MAJOR HOLIDAYS OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

The majority of Banyankole celebrate Christian holidays, including Christmas (December 25) and Easter (in March or April).

RITES OF PASSAGE OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

Traditionally, in early childhood, children began to learn the colors of cows and how to differentiate their families' cows from those of other homesteads. Boys were taught how to make water buckets and knives.

Girls were taught how to make milk-pot covers and small clay pots. By seven or eight years of age, boys were taught how to water cattle and calves. Girls helped by carrying and feeding babies. They were also expected to wash milk-pots and churn butter.

Among the Bahima (the herders), girls began to prepare for marriage as early as eight years of age. They were kept at home and given large quantities of milk in order to grow fat. Today, heaviness is still valued.

Among the Banyankole, the father's sister was (and still is) responsible for the sexual morality of the adolescent girl. Nowadays schools, peer groups, popular magazines, and other mass media are rapidly replacing family members as sources of moral education for teenagers.

Traditionally, adulthood was recognized through the establishment of a family by marriage. The acquisition of large herds of cows for Bahima and of abundant crops for Bairu (farmers) were other markers of adulthood. Full adult status was achieved through the rearing of a large family.

RELATIONSHIPS OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

Social relations among the Banyankole cannot be understood apart from rank. In the wider society, the Mugabe (king) and chiefs had authority over herders (Bahima).

The Bahima had authority over the Bairu (farmers). Within the family, husbands had authority over wives, and older children had authority over younger ones. Inheritance typically involved the eldest son of a man's first wife, who succeeded to his office and property.

Relations between fathers and sons and between brothers were formal and often strained. Mothers and their children, and brothers and their sisters, were often close.

Social relations in the community centered around exchanges of wealth, such as cows and agricultural produce.

The most significant way that community solidarity was and still is expressed is through the elaborate exchange of formalized greetings. Greetings vary by the age of the participants, the time of day, the relative rank of the participants, and many other factors. Anyone meeting an elder has to wait until the elder acknowledges that person first.

LIVING CONDITIONS OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

The traditional house of hima lof banyankole tribe

The traditional house of hima lof banyankole tribeThe Mugabe's (king's) homestead was usually constructed on a hill. It was surrounded by a large fence made from basketry. A large space inside the compound was set aside for cattle.

Special places were set aside for the houses of the king's wives, and for his numerous palace officials. There was a main gate through which visitors could enter, with several smaller gates for the entrance of family members.

Traditionally, Bahima (herders) maintained homes modeled after the king's but much smaller. The Bairu (farmers) traditionally built homes in the shape of a beehive. Poles of timber were covered with a framework of woven straw. A thick layer of grass frequently covered the entire structure.

Today, housing makes use of indigenous materials such as papyrus, grass, and wood. Homes are primarily rectangular. They are usually made from wattle and daub (woven rods and twigs plastered with clay and mud) with thatched roofs. Cement, brick, and corrugated iron are used by those who can afford them.

FAMILY LIFE OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

pre-marital virginity was valued.

pre-marital virginity was valued.Among the Bahima, a young girl was prepared for marriage beginning at about age ten, though sometimes as early as eight. Marriages often occurred before a girl was sexually mature, or soon after her initial menstruation.

For this reason, teenage pregnancies before marriage were uncommon. Polygyny (multiple wives) was associated with rank and wealth. Bahima herders who were chiefs typically had more than one wife, and the Mugabe (king) sometimes had over one hundred.

Marriages were alliances between clans and large extended families. Among both the Bahima and the Bairu, pre-marital virginity was valued.

Today, Christian marriages are common. The value attached to extended families and the importance of having children have persisted as measures of a successful marriage.

Monogamy is now the norm. Marriages occur at a later age than in the past, due to the attendance at school of both girls and boys. As a consequence, teenage pregnancies out of wedlock have risen.

Girls who become pregnant are severely punished by being dismissed from school or disciplined by parents. For this reason, infanticide is now more common than in the past, given that abortion is not legal in Uganda.

CLOTHING OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

The Traditional dressing style of the banyankole in Uganda

The Traditional dressing style of the banyankole in UgandaDress differentiates Banyankole by rank and gender. Chiefs traditionally wore long robes of cowskins. Ordinary citizens commonly were attired in a small portion of cowskin over their shoulders. Women of all classes wore cowskins wrapped around their bodies.

They also covered their faces in public. In modern times, cotton cloth has come to replace cowskins as a means of draping the body. For special occasions, a man might wear a long, white cotton robe with a Western-style sports coat over it.

A hat resembling a fez may also be worn. Today, Banyankole wear Western-style clothing. Dress suitable for agriculture such as overalls, shirts, and boots is popular. Teenagers are attracted to international fashions popular in the capital city of Kampala.

FOOD OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

The Plantain , on of the best food of the banyankole

The Plantain , on of the best food of the banyankoleBahima herders consume milk and butter and drink fresh blood from their cattle. The staple food of a herder is milk. Beef is also very important. When milk or meat are scarce, millet porridge is made from grains obtained from the Bairu. Buttermilk is drunk by women and children only. When used as a sauce, butter is mixed with salt, and meat or millet porridge is dipped into it.

Children can eat rabbit, but men can eat only the meat of the cow or the buffalo. Herders never eat chicken or eggs. Women consume mainly milk, preferring it to all other foods.

Cereals domesticated in Africa—millet, sorghum, and eleusine—dominate the agricultural Bairu sector. The Bairu keep sheep and goats. Unlike the herders, the farmers do consume chickens and eggs.

EDUCATION OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

Education among the banyankole

Education among the banyankoleIn the past, girls and boys learned cultural values, household duties, agricultural and herding skills, and crafts through observation and participation.

Instruction was given where necessary by parents; fathers instructed sons, and mothers instructed daughters. Elders, by means of recitation of stories, tales, and legends, were also significant teachers.

Formal education was introduced in Uganda in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Today, Ankole has many primary and secondary schools maintained by missionaries or the government.

In Uganda, among those aged fifteen years and over, about 50 percent are illiterate (unable to read or write). Illiteracy is noticeably higher among girls than among boys. Teenage pregnancy often forces girls to end their formal education.

Schools in Ankole teach the values and skills needed for life in modern-day Uganda. At the same time, schools seek to preserve indigenous (native) Ankole cultural values. The Runyankole language is taught in primary schools.

CULTURAL HERITAGE OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

All schools have regular performances and competitions. They involve dances, music, and plays. Where appropriate, instruction also makes use of Ankole folklore and artistic expression.

EMPLOYMENT OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

Cattle Keeping, one of the traditional employment of the banyankole people

Cattle Keeping, one of the traditional employment of the banyankole peopleAmong the Bahima, the major occupation was tending cattle. Every day the herder traveled great distances in search of pasture. Young boys were responsible for watering the herd. Teenage boys were expected to milk the cows before they were taken to pasture.

Women cooked food, predominantly meat, to be taken daily to their husbands. Girls helped by gathering firewood, caring for babies, and doing household work. Men were responsible for building homes for their families and pens for their cattle.

Among the Bairu, both men and women were involved in agricultural labor, although men cleared the land. Millet was the main food crop.

Secondary crops were plantains, sweet potatoes, beans, and groundnuts (peanuts). Maize (corn) was considered a treat by the children. Children participated in agriculture by chasing birds away from the fields.

SPORTS OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

Soccer Sports among the Banyankole

Soccer Sports among the BanyankoleSports, such as track and field and soccer, are very popular in primary and secondary schools. Children play an assortment of games including hide-and-seek, house, farming, wrestling, and ball games such as soccer. Ugandan national sporting events are followed with great interest in the Ankole region, as are international sporting events.

RECREATION OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

Radio and television are important means of entertainment in Ankole. Most homes contain radios that have broadcasts in English, KiSwahili (the two national languages), and Runyankole. Books, newspapers, and magazines also are popular.

Social events such as weddings, funerals, and birthday parties typically involve music and dance. This form of entertainment includes not only modern music, but also traditional forms of songs, dances, and instruments.

The drinking of alcoholic and nonalcoholic bottled beverages is common at festivities. In the past, the brewing of beer was a major home industry in Ankole.

CRAFTS AND HOBBIES OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

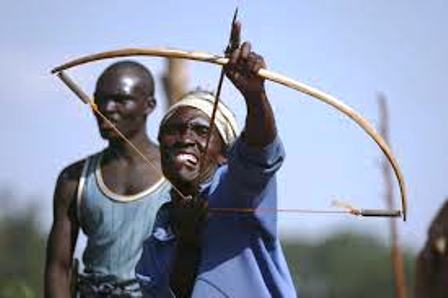

ironworkers, like bow and arrows for hunting

ironworkers, like bow and arrows for huntingCarpenters, ironworkers, potters, musicians, and others were once permanent features of the Mugabe's (king's) homestead or were in constant contact with it. Carpenters fashioned stools, milk-pots, meat-dishes, waterpots, and troughs for fermenting beer.

Iron-smiths manufactured spears, knives, and hammers. Every family had a member who specialized in pottery. Pipes for smoking displayed the finest artistic creativity. Small colored beads were used to decorate clay pipes, which came in various shapes and sizes, and walking sticks.

Traditional industries are not nearly as significant as in the past. Nevertheless, one can still observe the use of traditional pipes, water-pots for music, decorated walking sticks exchanged at marriage, and the use of gourds and pottery.

SOCIAL PROBLEMS OF NYANKOLE PEOPLE IN OF UGANDA

Health and Preventive Measures among the Banyankole

Health and Preventive Measures among the BanyankoleMilton Obote ruled Uganda from 1962 until 1971, when he was overthrown by Idi Amin. Obote prohibited the formation of ethnic kingdoms within Uganda. During Idi Amin's dictatorship in the 1970s, all Ugandans suffered from political oppression and the loss of life and property.

Obote once again took over in 1980 after the overthrow of Amin and ruled oppressively. Resistance to Amin and Obote resulted in the destruction of towns and villages. Uganda is currently working toward economic recovery and democratic reform.

Since the mid-1980s, AIDS has been a serious problem. As adult Ugandans die of AIDS, many children become orphans. There has been a strong national effort to educate the public through mass media about AIDS prevention.

A growing population, in spite of AIDS, remains a threat to a pastoral way of life. Warfare in neighboring countries such as Rwanda has contributed to population growth, as refugees have regularly come into the region.

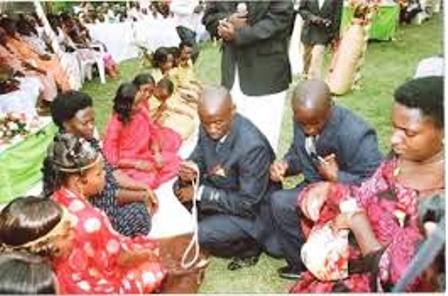

Ankole People traditional marriage

The Kuhingira a traditional Ankole People marriage

The Kuhingira a traditional Ankole People marriageThe Banyankole of South-Western Uganda are known for their culture-rich marriage; the Kuhinjira. Kuhinjira is a gifts giving pre-wedding ceremony of the Bafumbira Tribe from south western Uganda. The brides’ family gives gifts to the grooms’ family.

The common thread in the Ankole marriage like many African traditional marriages is to create closeness to the bridal family.

This is done through a third party called the Kateraruume (literally meaning somebody who will remove the dew from the path). The Kateraruume is a highly respected person representing the groom's interests and is charged with facing the bride’s family and ensuring that the bride’s family is willing to accept the groom’s family to formally discuss the marriage.

In case the proposal is endorsed, the man's family approaches the girl’s family with the Kateraruume leading them there.

At the home of the bride’s family, the go-between knocks at the gate and is invited in with the groom entourage after some teasing. The entourage usually comes with beer.The Kateraruume then indicates to the girl’s marriage panel that he is on a marriage mission.

The go-between then explains his mission and is asked many questions by the girl's family. Later, they discuss the marriage payments, which can be picked anytime after the two families have agreed, sometimes on that same day.

This is followed by preparations for marriage.In Ankole tradition, the marriage payment included cattle, which may go to over 10. These gifts are presented to the bride’s family symbolizing the ability of the groom to take care of his woman.

Unlike today where the men feel cheated by paying bride price, in the typical Ankole tradition, a groom gains from the marriage. Actually, the gifts (the emihingiro) that the bride comes with sometimes are more than those paid by the groom as bride price.

For example, among the Bahima-Banyankole, the aunties and uncles give cows to the bride during the kuhingira.

Younger girls and boys called the enshagarizi then escort the bride to the groom’s place after the blessings from the elders. Today, the groom’s side has to organise the transport for these people because they are very important for any marriage ceremony in Ankole.

Going back is not necessarily the role of the bridegroom. After the kuhingira, the bride’s side is still in control though. The bride according to the culture is not supposed to do any work until the cultural initiation. This is done after about ten days from the giveaway day.

During this initiation, the bride is made to light fire in the kitchen in the tradition called okukoza omumuriro (helping the bride to start toughing fire).

Because of modernity however, some brides have left the bridal room (orusika) the day after marriage to continue looking for a living in the competitive world where every minute lost contributes a lot to poverty in the homes.

Many people in Uganda may find it hard to understand the Ankole culture and language but many know the words okwanjura, okushwera and okuhingira irrespective of the language they speak.

History of the Ankole Kingdom

Bagyendanwa, The Royal Drum of Ankole Kingvdom

Bagyendanwa, The Royal Drum of Ankole KingvdomSome scholars believe that Ankole originally was occupied by Bantu-speaking agricultural Bairu. Later, Ankole provided a passage for Hamitic peoples, possibly the Bahima, migrating from Ethiopia southward. These pastoralists conquered the Bairu and proclaimed themselves the rulers of the land.

According to some scholars, the more numerous Bairu were serfs and the Bahima were the dominant ruling class. For the most part the two ethnic groups coexisted peacefully.

When the British created Uganda as a protectorate in 1888, Ankole was a relatively small kingdom ruled by a king (Mugabe) with supreme power.

In 1901 the British enlarged the kingdom by merging it with the similarly small kingdoms of Mpororo, Igara, Buhweju, and Busongora.

The power of the Omugabe was curtailed considerably once his kingdom was legally and constitutionally controlled. However, as the Omugabe of Ankole, the king was entitled to all the titles, dignities, and preeminence that were attached to his office under the laws and customs of Ankole.

A political relationship based on serfdom, slavery, and clientship ceased to exist under British rule, and the Bairu became less marginalized and despised.

The pastoralist Hima (also known as Bahima) established dominion over the agricultural Iru (also known as Bairu) some time before the nineteenth century. The Hima and Iru established close relations based on trade and symbolic recognition, but they were unequal partners in these relations.

The Iru were legally and socially inferior to the Hima, and the symbol of this inequality was cattle, which only the Hima could own. The two groups retained their separate identities through rules prohibiting intermarriage and, when such marriages occurred, making them invalid.

The Hima provided cattle products that otherwise would not have been available to Iru farmers. Because the Hima population was much smaller than the Iru population, gifts and tribute demanded by the Hima could be supplied fairly easily.

These factors probably made Hima-Iru relations tolerable, but they were nonetheless reinforced by the superior military organization and training of the Hima.

The kingdom of Ankole expanded by annexing territory to the south and east. In many cases, conquered herders were incorporated into the dominant Hima stratum of society, and agricultural populations were adopted as Iru or slaves and treated as legal inferiors. Neither group could own cattle, and slaves could not herd cattle owned by the Hima.

Ankole society evolved into a system of ranked statuses, where even among the cattle-owning elite, patron-client ties were important in maintaining social order. Men gave cattle to the king (mugabe) to demonstrate their loyalty and to mark life-cycle changes or victories in cattle raiding.

This loyalty was often tested by the king’s demands for cattle or for military service. In return for homage and military service, a man received protection from the king, both from external enemies and from factional disputes with other cattle owners.

The mugabe authorized his most powerful chiefs to recruit and lead armies on his behalf, and these warrior bands were charged with protecting Ankole borders. Only Hima men could serve in the army, however, and the prohibition on Iru military training almost eliminated the threat of Iru rebellion.

Iru legal inferiority was also symbolized in the legal prohibition against Iru owning cattle. And, because marriages were legitimized through the exchange of cattle, this prohibition helped reinforce the ban on Hima-Iru intermarriage.

The Iru were also denied highlevel political appointments, although they were often appointed to assist local administrators in Iru villages.

The Iru had a number of ways to redress grievances against Hima overlords, despite their legal inferiority. Iru men could petition the king to end unfair treatment by a Hima patron. Iru people could not be subjugated to Hima cattle-owners without entering into a patron-client contract.

A number of social pressures worked to destroy Hima domination of Ankole. Miscegenation took place despite prohibitions on intermarriage, and children of these unions (abambari) often demanded their rights as cattle owners, leading to feuding and cattle-raiding.

From what is present-day Rwanda groups launched repeated attacks against the Hima during the nineteenth century. To counteract these pressures, several Hima warlords recruited Iru men into their armies to protect the southern borders of Ankole.

Death and Afterlife Perception of the Banyankole People

Among the Banyankole illness is not considered a natural cause of death; therefore, such deaths require an investigation to find the responsible party.

By contrast, old age is accepted as a sufficient cause for death. It is held that God allows old people to die after the completion of their time on earth. The Banyankole view death as a passage to another world.When a man dies, every relative, along with friends and neighbors, is informed.

A person who fails to attend the funeral without a good reason may be suspected of being associated with the death. Before burial, the body is washed and the eyes are closed.

As the deceased is placed in the grave, the right hand is placed under the head while the left hand rests on the chest. The body lies on the right side.

One or more cows are slaughtered to feed everyone present. Beer is provided as part of the mourning. The mourning goes on for four days. A deceased woman is treated in a similar manner except that in the grave she is made to lie on the left side as if she were facing her husband.

Other Pages of Interest

Kenya Cultural Origins |

Kenya Student Rules |

Kikuyu People |

Luo in Kenya |

Masai People |

Samburu People |

Student Class Rules |

Turkana People in Kenya |

Recent Articles

-

Garam Masala Appetizers ,How to Make Garam Masala,Kenya Cuisines

Sep 21, 14 03:38 PM

Garam Masala Appetizers are originally Indian food but of recent, many Kenyans use it. Therefore, on this site, we will guide you on how to make it easily. -

The Details of the Baruuli-Banyara People and their Culture in Uganda

Sep 03, 14 12:32 AM

The Baruuli-Banyala are a people of Central Uganda who generally live near the Nile River-Lake Kyoga basin. -

Guide to Nubi People and their Culture in Kenya and Uganda

Sep 03, 14 12:24 AM

The Nubians consist of seven non-Arab Muslim tribes which originated in the Nubia region, an area between Aswan in southern

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.