Busoga People and their Culture in Uganda

Who are the Basoga People in Uganda? The Soga are the eastern neighbors of the Baganda.

They occupy the region between Lake Victoria and Lake Kioga the present districts of Kamuli, Jinja and Iganga. They make up about 8 per cent of the population.

Before the arrival of the Europeans, they had been subsistence farmers who also kept cattle, sheep, and goats.

They commonly maintained gardens for domestic use close to the homestead.

Early inhabitants of this region were Nilo-Hamitic tribes like the Langi und Iteso as well as the Bagisu (a Bantu tribe).

Subsequently, the Soga who had immigrated from the East expelled them and also adopted their traditions and lifestyle.

The clan chiefs defined daily life in the society, and they distributed land for cultivation.

Spiritual rites were performed by those authorized.

Ancestral worship was also practised, and many gods and semi-gods as well as Lubaale, their creator, were worshipped.

In general, they believed in animated nature which had to be offered sacrifices.Later on, the Soga got under the influence of the Baganda, as their dialect Luanda was closely related with the Busoga dialect Lusoga and as it was commonly used.

The Baganda dialect prevailed, as the Soga dialects were hard to understand by members of other Soga tribes.

According to a legend the excellent hunter Mukama immigrated with his entourage from the East into this region and assumed power here; his influence was even felt in the neighbouring Bunyoro.

Supposedly, his son, who had been given the same name, stayed behind when his father moved on and ruled over Bunyoro. According to another legend, Kintu's son Mukama was left behind here as ruler, when his tribe moved on to Buganda.

Traditionally, the Busoga society consisted of a number of small kingdoms, and they were not united under a single paramount leader.

The community was organised around a number of principles, the most important of which was descent. Descent was traced through male ancestors, leading to the formation of the patrilineage, which included an individual's closest relatives.

This group provided guidance and support for each individual and united related homesteads for economic, social, and religious purposes. The women of the household cared for the most common staple foods, this is bananas, millet, cassava, and sweet potatoes.

Men generally cared for cash crops, these being coffee, cotton, peanuts, and corn. Lineage membership determined marriage choices, inheritance rights, and obligations to worship the ancestors.

An individual usually attempted to improve his economic and social position, which was initially based on lineage membership, by skillfully manipulating patron-client ties within the authority structure of the kingdom.

A man's patrons, as much as his lineage relatives, influenced his status in society. Unlike the Kabakas (kings) of the Buganda, Busoga kings are members of a royal clan, selected by a combination of descent and approval by royal elders.In northern Busoga, near Bunyoro, the royal clan, the Babiito, is believed to be related to the Bito aristocracy in Bunyoro. Some Basoga in this area are convinced that their ancestors are the people of Bunyoro.

What are their origins

Due to the continuous movements and intermingling of the people within that region, the history of these people is complex.

It can be asserted however that the earliest inhabitants of Busoga belonged to the same Bantu group comprising the Batooro and Baganda.

Their origin can therefore be traced like other Bantu groups to the Katanga region of Central Africa.

Tradition holds that the earliest in habitants were the langi; the Iteso and Bagishu.

They were later engulfed by migrants from Buganda.

The earliest settlers in Busoga are said to have occupied Lake-shore areas of modern Bukoli Nyanyumba’s Banyankole are believed to have been among these earliest inhabitants.

These early settlements took place far back in the 14th century. They were later joined by other people from Mt. Elgon region.

These people are said to have been led by Kintu and are said to have settled in Bugabula and Bulamogi. They were later joined by others from Budama and some from Kigulu in Kenya.

Their traditional legend

There are three legends regarding the origins of the Basoga. One of them talks of the famous hunter, Mukuma, who came from the East side of Mt Elgon and crossed via present Bugishu and Budama. He is said to have been accompanied by his wife, various followers and two dogs.

Mukuma had eight sons during his stay in Busoga. These sons were subsequently appointed rulers over certain areas.

Mukuma preceded to Bunyoro were he set up a Kingdom. He died of smallpox and that is why the relatives of Mukuma in Busoga do not look at a patient with small pox.It is also customarily that no member of the Ngobi clan passes another one with smallpox without touching him.

The second legend insists that Mukuma did not come to Busoga at all that Mukuma only sent his sons to rule Busoga because there were no capable rulers in Busoga.The third legend talks of Kintu having been the man called Mukama and it was this same Kintu who came to Busoga from the east of Mt Elgon.

This legend asserts that Kintu left his sons in Busoga and continued to Buganda. He is said to have returned to Busoga and lived in a place called Buswikira which is at Igombe, Bunya.

He died and was buried there. Afterwards, his tomb became a rock which is worshiped even today by some people.

Originally, these people were a disunited people. They could not unite even in the face of a common enemy. This explains why they were incessantly prone to foreign influence first from Bunyoro and later form Buganda.

Traditional basoga religion

The Basoga believed in the existence of a spirit world.

They called the Supreme Being lubaale. Human agents worked as messengers of Lubaale, or the ancestors, or other minor gods.

To the Basoga, the spirit world, places of worship, animated objects and fetishes had power to do good or evil to the living.

The Basoga call magicians, fetishmen and spirit mediums BachweziThe Basoga believed in the existence of gods and sub-gods.

Below lubaale, there were mukama the creator of all things; Jingo, the public god who attended to the general needs of the people; Nawandyo; and Bilungo the god of plagues. Semanda, Gasani and Kitaka were other gods the Basoga believed in.

The King and History of Busoga Kingdom

Busoga is ruled by the His Royal Highness Isebantu Kyabazinga of Busoga. This name was a symbol of unity derived from the expression and recognition by the Basoga that their leader was the “father of all people who brings all of them together”, and who also serves as their cultural leader.

History of Busoga Kingdom

Written history begins for Busoga in the year 1862. On 28 July 1862, John Hanning Speke, an explorer for the Royal Geographical Society, arrived at Ripon Falls, near the site of the modern town of Jinja, where the Victoria Nile spills out of Lake Victoria and begins its descent to Egypt.

Since Speke’s route inland from the East African coast had taken him around the southern end of the lake Victoria, he approached Busoga from the west through Buganda. Having reached his goal – the source of the Nile, he turned northward and followed the river downstream without further exploring Busoga.

He records, however, being told that “Usoga”(the Swahili form of the name “Busoga”) was an “island”, which indicates that the term meant to surrounding peoples essentially what it means today.

The present day Busoga Kingdom was, and still is, bounded on the north by the swampy Lake Kyoga, on the west by the Victoria Nile, on the south by Lake Victoria, and on the east by the Mpologoma River.

In the 19th century, one of the principal routes along which Europeans travelled from the coast to Buganda passed through the southern part of Busoga.

From John Speke and James Grant, Sir Gerald Portal, F.D Lugard, J.R. Macdonald, and Bishop Tucket all noted that Busoga was plentifully supplied with food and was densely settled as a result. However, between 1898–99 and 1900-01, the first indications of sleeping sickness were reported.

In 1906, orders were issued to evacuate the region. Despite the attempts to clear the area, the epidemic continued in force until 1910.

As a result, most of the densely populated parts of Busoga, the home land of over 200,000 persons in the 19th Century, was totally cleared of the population in the ten years.

Lubas palace at Bukaleba, also the coveted European fruit mission, collapsed and relocated to other parts of Busoga. Southern Busoga constituted of about one third of the land area of Busoga, and, in 1910, southern Busoga was vacant.

In the 1920s and 1930s, some of the evacuees who survived the epidemic began to return to their original land. However, in 1940 a new outbreak of sleeping sickness resurfaced in the area, and it was only in 1956 that resettlement, promoted by the government began again, but things were not going to be the same again. Few Basoga returned to their traditional lands.

Political status of the basoga people in uganda

About the turn of the 16th century, an important event took place, which was to give the Basoga their peculiar cultural configuration. This was the advent of the Baisengobi clan, who bear their historical descendancy from Bunyoro.

Prince Mukama Namutukula from the royal family (Babiito) of Bunyoro is said to have left Bunyoro around the 16th century and as part of Bunyoro’s expansionist policy and trekked eastwards across Lake Kyoga with his wife Nawudo, a handful of servants, arms and a dog, and landed at Iyingo, located at the northern point of Busoga in the present day Kamuli District.

Prince Mukama loved hunting and his adventures exposed him to the beauties of the new found land. For some time he engaged himself in blacksmithing, making hoes, iron utensils and spears. Prince Mukama and wife Nawudo bore several children of whom only five boys survived.

On his departure back to Bunyoro, Prince Mukama allocated them areas within his influence as overseers. The five sons of Prince Mukama regarded themselves as the legitimate rulers over their respective areas by virtue of their family origin (Babiito).

They continued to preside over their respective dominions; employing governing methods and cultural rituals like those from Bunyoro-Kitara.

This state of affairs in Busoga’s political and cultural arrangement continued till the late 19th century when the colonialists persuaded the rulers of Busoga into some form of federation. This federation resulted into a regional Busoga council called Busoga Lukiiko.

Before 1906, although it was often called a ‘Kingdom’, it was debatable whether Busoga could really be classified as such. Unlike its western neighbor, Buganda, Busoga did not have a central ‘all-powerful’ figurehead (King or Queen) until 1906, at the behest of the British colonial powers.

Prior to this, the Basoga were organized in semi-autonomous chiefdoms, partly under the influence of Bunyoro initially, and then later on, under the partial influence of Buganda.

Before the coming of the British to Uganda, there was no uniting leadership in Busoga. When Uganda became a British protectorate, attempts were made to create a central form of administration on the model of Buganda which was a fully fledged kingdom.

The Buganda King – the Kabaka had lineage going back centuries. However, in Busoga some of the chiefs had been simply appointed by the Kabaka – and it is believed that in some cases they were descendants of favored Baganda chiefs who were given authority to rule over land in Busoga.

Others simply belonged to powerful landowning families in Busoga that had become self-appointed rulers over vast areas. The British brought all these chiefs into an administrative structure called the Lukiiko.

The British appointed a Muganda from Buganda, Semei Kakungulu as the President of the Lukiiko and he became Busoga’s first leader, although the British refused to give him the title of ‘King’, as they did not regard him as a real king.

However wrangles amongst the different chiefs and clans continued, and most Basoga still retained affiliation to their chief, clan or dialect. It was also not helpful that the ‘King’ was from Buganda.

The Lukiiko structure collapsed. The structure had however given the Basoga a taste of what influence they could muster in the protectorate if they had a King. It would elevate them to the level of Bunyoro and Buganda.

Meanwhile, the white colonial rulers were grooming Chief Yosia Nadiope, the Gabula of Bugabula to become the first permanent resident ruler of the formed Busoga federation. Nadiope had been one of the first Basoga students to study at Kings College Budo in 1906.

However, catastrophe struck Busoga in 1913, when Nadiope died of malaria. The following year 1914, Chief Ezekeriel Tenywa Wako, the Zibondo of Bulamogi was completing his studies at Kings College Budo. With the support of the British coupled with his background as a Prince, Zibondo of Bulamogi, with his good educational background, was a suitable candidate for the top post.

In 1919, the hereditary saza chiefs of Busoga resolved in the Lukiiko to elect Ezekerial Tenywa Wako as president of Busoga. Chief Gideon Obodha of Kigulu, a contending candidate for the post was not familiar with the British system, while William Wilberforce Nadiope Kadhumbula of Bugabula was still an infant. His regent Mwami Mutekanga was a ‘mukoopi’ (a commoner) who couldn’t run for the post.

Eventually, in 1918-9, the title of Isebantu Kyabazinga was created and one of the chiefs, Wako took the throne. He was given a salary of 550 pounds, and permitted to collect taxes in Butembe county in lieu of the lost role in his traditional chiefdom of Bulamogi.

In 1925, Ezekiel Tenywa Wako, the Kyabazinga of Busoga became a member of Uganda Kings Council, consisting of the Kyabazinga of Busoga, Kabaka of Buganda, the Omukama of Bunyoro, Omukama of Toro/Omukama of Tooro and Omugabe of Ankole.

On 11 February 1939 Owekitibwa Ezekerial Tenywa Wako (late father of the last Isebantu Kyabazinga wa Busoga, HRH Henry Wako Muloki), the Zibondo of Bulamogi was installed as the first Isebantu Kyabazinga wa Busoga which title he continued to hold until 1949 when he retired due to old age.

By the time Owekitibwa E.T. Wako retired as the Isebantu Kyabazinga wa Busoga, the Busoga Lukiiko had expanded to include people other than the Hereditary Rulers. These members of the Busoga Lukiiko were elected representatives – two from each of the then 55 Sub-counties in Busoga.

When Owekitibwa E.T.Wako retired, it was necessary to replace him. The Busoga Lukiiko resolved then that the Isebantu Kyabazinga wa Busoga shall always be elected among the five lineages of Baise Ngobi (Ababiito) hereditary rulers – traditionally believed to have been the five sons of Omukama of Bunyoro who immigrated to Busoga from Bunyoro.

This method of election was used for the subsequent elections of the Isebantu Kyabazinga wa Busoga, beginning 1949 when Owekitibwa Chief William Wilberforce Nadiope Kadhumbula of Bugabula was elected Isebantu Kyabazinga wa Busoga for two terms of three years each, followed by Owekitibwa Henry Wako Muloki who also served two terms.

In 1957, the title Inhebantu was introduced as a description of the wife of the Isebantu. This epitomised the gradual unification of Busoga and the evolution of Obwa Kyabazinga bwa Busoga.

When monarchies were abolished in 1966, the Kyabazinga was dethroned. When Idi Amin expelled the Asians from Uganda in 1972, Jinja suffered both socially and economically. The government of Yoweri Museveni has tried to encourage Ugandan Asians to return. This has helped but has not revitalized Jinja to its former glory. However the Asian influence remains, particularly in the architecture and street names.

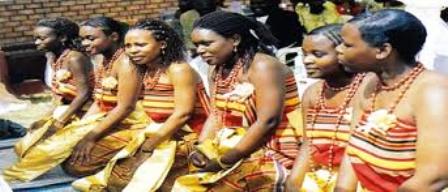

Traditional Marriages Among the Basoga People of Uganda: (Okuzaaliibwa Mumaka)

Traditional Marriages Among the Basoga People of Uganda

Traditional Marriages Among the Basoga People of UgandaIdentifying a wife

According to Amos Mukwaya an elderly resident of Bugembe in Jinja, traditionally, a Musoga man would identify a girl he wanted to marry and subsequently send an advance team comprising mainly of presentable and honourable male members of his family or clan.

This team would be charged with getting in contact with the girl's family and gathering information about her to avoid marriages between members of the same clan.

This is because, as is the case with many Ugandan tribes, people from the same clan consider themselves as siblings," Mukwaya explains

The team of emissaries would table a formal request to introduce their son and ask for the girl's hand in marriage (okuzaliibwa mumaka).

Nowadays, this is done through a letter to the family head and is delivered by the girl herself. The father does not read it alone but solicits the company of his sister while reading it.

The letter always suggests a specific date on which the man intends to present himself for proper introduction. If inconvenient for the girl's family, an alternative date is chosen and communicated to the man's family in the reply.

Mention of refunds for items and costs the girl's family will incur in hosting the man's entourage is made in the same reply, which is delivered by the bride to the groom.

The significance of the introduction ritual (Okuzaalibwa mumaka) is enhanced by the fact that the Basoga always have a particular interest in knowing and vetting their prospective in-laws.

This ritual, therefore, is a way of creating a bond that unites both families. For a mysterious man to declare himself part of the girl's family without official recognition was considered a taboo and was severely punishable.

The bride communicates to her parents the progress of the eminent visit from their prospective son-in-law and her parents respond positively by providing a list of possible gifts to be brought by the man on the big day.

Unlike today, the girls in Busoga were always keen on preserving their purity and sanctity for their future husbands. A girl was expected to remain a virgin until she was formally married.

Before the introduction ceremony, gifts like kanzu (tunics) for the girl's father, busuuti for her mother, paternal auntie and one for the daadaa (grandmother) and any others as may be seen fit are bought by the groom.

Different envelopes containing money may be prepared, each meant for a specific branch of the bride's family.

As preparations for okuzaalibwa mumaka move into high gear, the girl stays in closer touch with her family and advises her prospective husband on which gifts to buy.

If financial relief is needed by the girl's family to prepare for the big day, her parents will, again through their daughter, request for the same.

Basoga wives are generally known to be submissive to their husband's wishes and are fond of saying Omwaami kyakoba, nzeena kyenkoba (What my husband says holds for me too).

However, initially it is the girl who calls the tune and the groom dances as she is the only link between the groom's family and hers. She may edit the list of gifts her man is to bring to her parents into a more expensive one.

Contrary to what is practiced by most other ethnic groups in Uganda, the Basoga do not hold ceremonies for setting the amount of bride price to be paid for their daughter, as this is communicated through their daughter, specifying their expectations and interests.

The girl, who always has good knowledge of what her parents prefer, guides the groom on what kind of gifts to buy.

Traditionally, the girl's parents were always keen on exploiting the opportunity of getting bride price by demanding a big amount of either cattle or money.

The fortune accumulated from the girl's bride price was always saved to pay for her brothers' bride price when it was their turn to pay for someone else's daughters.

Unlike the practice in Buganda, pre-okuzaalibwa mumaka visits to the girl's homestead by the groom are not entertained.

Such visits are considered immoral in the sense that it would then seem like the young couple is already indulging in secret acts of marriage.

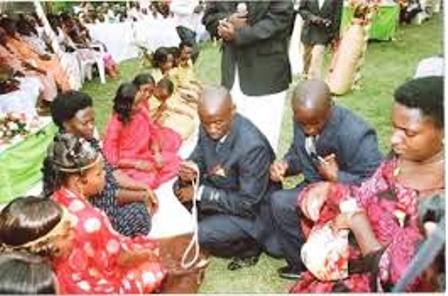

On the big day, the groom and his entourage composed mainly of his family, depart for the girl's parent's homestead, armed with such gifts as her father's kanzu (tunic), her mother's gomesi (ladies' cultural garb), envelopes stuffed with money for the girl'sbaseenga, bamaama, bakoojja and babaaba abaato (paternal aunties, maternal aunties, maternal uncles and paternal uncles respectively) and any other gifts that may have been requested.

They should endeavor to keep time. If they arrive later than the agreed time, the entrance to the enganguu (reception venue) will certainly be closed to them. It may take skillful negotiations oiled by paying a 'fine' to convince the gatekeeper to let them through.

Once received and allowed to take their seats, the entourage must stay still and remain silent, unless greeted by groups of the girl's family, after which they are requested to introduce themselves. Their spokesman then introduces them, one by one, as they stand up briefly for recognition.

That accomplished, their hosts will ignore the entourage until they pay ekivumbula mumwa (mouth opener), a token that may come in the form of money given to the spokesman of the hosts. Unless the token is impressive, the visitors will continue to be ignored.

The hosting side always dominates this session, asking the questions with the visitors making sure they answer carefully.

The hosting spokesman inquires from the girl if she knows the visitors and obtains her views about the visiting spokesman's carefully crafted proposals.

After getting familiar with the visitors, the hosting spokesman mentions a set of conditions and expectations upon which the issue of bride price can be discussed.

The girl's senga (paternal auntie) takes the floor and kneels in front of her prospective son-in-law, handing him a handkerchief containing some money.

The groom is expected to add double this amount of money and even exceed it by at least 10% before handing it back to the senga, or else she does not introduce him.

If impressed, she will take the floor again and say good things about the groom, after which the girl's father, if convinced, will show approval. Nice things about the girl's background will be mentioned and so will her father's expectations of a privileged new life for her if the groom marries her.

If the cultural conditions are also met, she is handed over to her suitor by her trusted brother and farewell bid to her.

With negotiations finished and dowry payments made or referred to a future date (which some affluent families use as a test of readiness by the man to marry their daughter), a typical Christian father is always keen to know about the plans for a church wedding or alternative ways of cementing the relationship.

That resolved, the traditional marriage ceremony is considered done and the couple will be separated for a while and the girl coached by her senga on her marital duties.

After this, the couple is now free to live together. Most families end the reception with a party until dawn.

Traditionally, weddings were conducted by an elder who administered a concoction of herbs and blessed the couple. At such ceremonies, animals were sacrificed to pay respect to and ask for the blessings of the ancestors, followed with a cultural dance and songs while congratulatory gifts were offered to the newly wed couple.

However, with the Basoga now being one of the most religiously influenced tribes in Uganda, contemporary marriages are predominantly religious, with couples seeking God's blessings in houses of worship, in the presence of chosen witnesses and religious leaders.

As with most Ugandan ethnic tribes, in Busoga children are the ultimate goal of a marriage and according to Akuuwa Ekiiboono, if a couple's relationship was barren, it was typical for the man to have an automatic a right to opt for a divorce or marry another wife.

Families in Busoga were (and still are) very patriarchal in setting, with men undertaking most of the family's financial obligations through fishing and agriculture, while the women concentrate on domestic chores with the help of their female offspring.

Divorce was usually always in favor of the males. However, only in extreme cases of adultery or barrenness was it enforced.

The fulfillment of procreation and a life, not of solitude but of unity, has always been a remarkable ideal of the Basoga and for this, they have a motto; Busoga etebenkele ni Kyabazinga afunvuwaale! (Long live Busoga and long live our King!)

Other Related Pages

Kenya Cultural Origins |

Kenya Student Rules |

Kikuyu People |

Luo in Kenya |

Masai People |

Samburu People |

Student Class Rules |

Turkana People in Kenya |

Recent Articles

-

Garam Masala Appetizers ,How to Make Garam Masala,Kenya Cuisines

Sep 21, 14 03:38 PM

Garam Masala Appetizers are originally Indian food but of recent, many Kenyans use it. Therefore, on this site, we will guide you on how to make it easily. -

The Details of the Baruuli-Banyara People and their Culture in Uganda

Sep 03, 14 12:32 AM

The Baruuli-Banyala are a people of Central Uganda who generally live near the Nile River-Lake Kyoga basin. -

Guide to Nubi People and their Culture in Kenya and Uganda

Sep 03, 14 12:24 AM

The Nubians consist of seven non-Arab Muslim tribes which originated in the Nubia region, an area between Aswan in southern

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.