Masai People of Kenya and their Culture

Masai people of Kenya are the most prominent people as far as African culture are concerned. On this page, It’s said that they are the most brave people in south of the Sahara.

This is exemplified by how they are living with wild animals like lions and other African big five on the same land where they graze their cattle. On this page we will guide you to know more about the culture of the Masai people in Kenya and their culture in Africa.

The Maasai (sometimes spelled "Masai" or "Masaai") are a Nilotic ethnic group of semi-nomadic people located in Kenya and northern Tanzania.

They are among the best known of African ethnic groups, due to their residence near the many game parks of East Africa, and their distinctive customs and dress.

They speak Maa (ɔl Maa), a member of the Nilo-Saharan language family those is related to Dinka andNuer, and are also educated in the official languages of Kenya and Tanzania: Swahili and English.

The Maasai population has been reported as numbering 841,622 in Kenya in the 2009 census,compared to 377,089 in the 1989 census.

The Tanzanian and Kenyan governments have instituted programs to encourage the Maasai to abandon their traditional semi-nomadic lifestyle, but the people have continued their age-old customs.

Recently, Oxfam has claimed that the lifestyle of the Maasai should be embraced as a response to climate change because of their ability to farm in deserts and scrublands.

Many Maasai tribes throughout Tanzania and Kenya welcome visits to their village to experience their culture, traditions, and lifestyle.

The Maasai are thought of as the typical cattle herders of Africa, yet they have not always been herders, nor are they all today.

Because of population growth, development strategies, and the resulting shortage of land, cattle raising is in decline.

However, cattle still represent "the breath of life" for many Maasai. When given the chance, they choose herding above all other livelihoods.

For many Westerners, the Maasai are Hollywood's "noble savage"—fierce, proud, handsome, graceful of bearing, and elegantly tall.

Hair smeared red with ochre (a pigment), they either carry spears or stand on one foot tending cattle.

These depictions oversimplify Maasai life during the twentieth century. Today, Maasai cattle herders may also be growing maize (corn) or wheat, rearing Guinea fowl, raising ostriches, or may be hired by ecologists to take pictures of the countryside.

Prior to British colonization, Africans, Arabs, and European explorers considered the Maasai formidable warriors for their conquests of neighboring peoples and their resistance to slavery. Caravan traders traveling from the coast to Uganda crossed Maasailand with trepidation.

However, in 1880–81, when the British unintentionally introduced rinderpest (a cattle disease), the Maasai lost 80 percent of their stock. The British colonizers further disrupted Maasai life by moving them to a reserve in southern Kenya.

While the British encouraged them to adopt European ways, they also advised them to retain their traditions.

These contradictions resulted, for the most part, in leaving the Maasai alone and allowed them to develop almost on their own.

However, drought, famine, cattle diseases, and intratribal warfare (warfare among themselves) in the nineteenth century greatly weakened the Maasai and nearly destrtoyed certain tribes.

Since Kenyan and Tanzanian independence from Britain in the 1960s, land ownership has changed dramatically. Modern ranching, wheat cultivation techiques, and setting of grazing boundaries in the Maasai district are becoming common.

A wage and cash economy is replacing the barter (trade) system. Consequently, the Maasai have begun to integrate themselves into the modern economies and mainstream societies of Kenya and Tanzania, albeit with considerable reluctance.

Origins / Location of the Maasai People in Kenya

The Maasai are thought to have originated in the Upper Nile Valley. Their myths speak about climbing up from a broad and deep crater bounded on all sides by a steep, long cliff. By the 1600s they had begun migrating with their herds into the vast arid, savanna-like (grassland) region of East Africa straddling the Kenya-Tanzania border.

Today, their homeland is bounded by Lake Victoria to the west and Mount Kilimanjaro to the east. Maasailand extends some 310 miles (500 kilometers) from north to south and about 186 miles (300 kilometers) at its widest east-west point.

Estimates of the Maasai population include more than 150,000 in Tanzania, and close to 150,000 in Kenya.

Language of the Maasai People in Kenya

The Maasai are speakers of the Maa language, which is also spoken by the Samburu and the Chamus living in central Kenya. The origins of Maa have been traced to the east of present-day Juba in southern Sudan. More than twenty variants of Maa exist. The Maasai refer to their language as Olmaa.

Traditional Folklore of the Maasai People in Kenya

Maasai legends and folktales tell much about the origin of present-day Maasai beliefs. These stories include their ascent from a crater, the emergence of the first Maasai prophet-magician (Laibon), the killing of an evil giant (Oltatuani) who raided Maasai herds, and the deception by Olonana of his father to obtain the blessing reserved for his older brother, Senteu (a legend similar to the Biblical story of Jacob and Esau).

One origin myth reveals much about present-day Maasai relations between the sexes. It holds that the Maasai are descended from two equal and complementary tribes, one consisting strictly of females, and the other of males.

The women's tribe, the Moroyok, raised antelopes, including the eland, which the Maasai claim to have been the first species of cattle. Instead of cattle, sheep, and goats, the women had herds of gazelles.

Zebras transported their goods during migrations, and elephants were their devoted friends, tearing down branches and bringing them to the women who used them to build homes and corrals.

The elephants also swept the antelope corrals clean. However, while the women bickered and quarreled, their herds escaped. Even the elephants left them because they could not satisfy the women with their work.

According to the same myth, the Morwak—the men's tribe—raised cattle, sheep, and goats. The men occasionally met women in the forest. The children from these unions would live with their mothers, but the boys would join their fathers when they grew up.

When the women lost their herds, they went to live with the men, and, in doing so, gave up their freedom and their equal status. From that time, they depended on men, had to work for them, and were subject to their authority.

Traditional Religion of the Maasai People in Kenya

Unlike the predominantly Christian populations of Kenya and Tanzania that surround them, the Maasai traditionally place themselves at the center of their universe as God's chosen people. Like other African religions, the Maasai believe that one high god (Enkai) created the world, forming three groups of people.

The first were the Torrobo (Okiek pygmies), a hunting and gathering people of small stature to whom God gave honey and wild animals as a food source. The second were the neighboring Kikuyu, farmers to whom God gave seed and grain.

The third were the Maasai, to whom God gave cattle, which came to earth sliding down a long rope linking heaven and Earth. While the Torrobo were destined to endure bee stings, and the Kikuyu famines and floods, the Maasai received the noble gift of raising cattle.

A Torrobo, jealous of the Maasai's gift of cattle, cut the "umbilical cord" between heaven and Earth. For many Maasai, the center of their world remains their cattle, which furnish food, clothing, and shelter.

Major Holidays of the Maasai People in Kenya

The traditional Maasai calendar has no designated holidays. It is divided into twelve months belonging to three main seasons: Nkokua (the long rains), Oloirurujuruj (the drizzling season), and Oltumuret (the short rains). The names of months are very descriptive.

For example, the second month of the drizzling season is Kujorok , meaning "The whole countryside is beautifully green, and the pasture lands are likened to a hairy caterpillar."

Maasai ceremonial feasts for circumcision, excision (female circumcision), and marriage offer occasions for festive community celebrations, which may be considered similar to holidays.

As the Maasai are integrated into modern Kenyan and Tanzanian life, they also participate in secular (nonreligious) state holidays.

In Kenya, these include Labor Day (May 1), Madaraka Day (June 1), and Kenyatta Day (October 20). In Tanzania, these include Labor Day (May 1), Zanzibar Revolution Day (January 12); Nane Nane (formerly Saba Saba— Farmer's Day, in August); Independence Day (December 9); and Union Day (April 26), which commemorates the unification of Zanzibar and the mainland.

Rites of Passage and Manhood initiations

Life for the Maasai is a series of conquests and tests involving the endurance of pain. For men, there is a progression from childhood to warriorhood to elderhood.

At the age of four, a child's lower incisors are taken out with a knife. Young boys test their will by their arms and legs with hot coals. As they grow older, they submit to tattooing on the stomach and the arms, enduring hundreds of small cuts into the skin.

Ear piercing for both boys and girls comes next. The cartilage of the upper ear is pierced with hot iron. When this heals, a hole is cut in the ear lobe and gradually enlarged by inserting rolls of leaves or balls made of wood or mud. Nowadays plastic film canisters may serve this purpose. The bigger the hole, the better. Those earlobes that dangle to the shoulders are considered perfect.

Circumcision (for boys) and excision (for girls) is the next stage, and the most important event in a young Maasai's life. It is a father's ultimate duty to ensure that his children undergo this rite.

The family invites relatives and friends to witness the ceremonies, which may be held in special villages called imanyat . The imanyat dedicated to circumcision of boys are called nkang oo ntaritik (villages of little birds).

Circumcision itself involves great physical pain and tests a youth's courage. If they flinch during the act, boys bring shame and dishonor to themselves and their family.

At a minimum, the members of their age group ridicule them and they pay a fine of one head of cattle. However, if a boy shows great bravery, he receives gifts of cattle and sheep.

Girls must endure an even longer and more painful ritual, which is considered preparation for childbearing. (Girls who become pregnant before excision are banished from the village and stigmatized throughout their lives.) After passing this test of courage, women say they are afraid of nothing.

Guests celebrate the successful completion of these rites by drinking great quantities of mead (a fermented beverage containing honey) and dancing.

Boys are then ready to become warriors, and girls are then ready to bear a new generation of warriors. In a few months, the young woman's future husband will come to pick her up and take her to live with his family.

After passing the tests of childhood and circumcision, boys must fulfill a civic requirement similar to military service. They live for up to several months in the bush, where they learn to overcome pride, egotism, and selfishness.

They share their most prized possessions, their cattle, with other members of the community. However, they must also spend time in the village, where they sacrifice their cattle for ceremonies and offer gifts of cattle to new households.

This stage of development matures a warrior and teaches him nkaniet (respect for others), and he learns how to contribute to the welfare of his community. The stage of "young warriorhood" ends with the eunoto rite, when a man ends his periodic trips into the bush and returns to his village, putting his acquired wisdom to use for the good of the community.

Relationships of the Maasai People in Kenya

Each child belongs to an "age set" from birth. To control the vices of pride, jealousy, and selfishness, children must obey the rules governing relationships within the age set, between age sets, and between the sexes.

Warriors, for example, must share a girlfriend with at least one of their age-group companions. All Maasai of the same sex are considered equal within their age group.

Many tensions exist between children and adults, elders and warriors, and men and women. The Maasai control these with taboos (prohibitions). A daughter, for example, must not be present while her father is eating.

Only non-excised girls may accompany warriors into their forest havens, where they eat meat. Although the younger warriors may wish to dominate their communities, they must follow rules and respect their elders' advice.

Traditional living Conditions of the Maasai People in Kenya

By Western standards, Maasai living conditions seem primitive. However, the Maasai are generally proud of their simple lifestyle and do not seek to replace it with a more modern lifestyle. Nevertheless, the old ways are changing.

Formerly, cowhides were used to make walls and roofs of temporary homes during migrations. They were also used to sleep on. Permanent and semi-permanent homes resembling igloos were built of sticks and branches plastered with mud, and with cow dung on the roofs.

They were windowless and leaked a great deal. Nowadays, tin roofs and other more modern materials are gradually transforming these simple dwellings.

A few paved trunk roads and many passable dirt roads make Maasailand accessible. Much like their fellow Kenyan and Tanzanian citizens, the Maasai travel by bus and bush taxi when they need to cover distances.

Family Life of the Maasai People in Kenya

The Maasai are a patriarchal society; men typically speak for women and make decisions in the family. Male elders decide community matters. Until the age of seven, boys and girls are raised together. Mothers remain close to their children, especially their sons, throughout life.

Once circumcised, sons usually move away from their father's village, but they still follow his advice. Girls learn to fear and respect their fathers and must never be near them when they eat.

A person's peers (age-mates) are considered extended family and are obligated to help each other. Age-mates share nearly everything, even their wives. Girls are often promised in marriage long before they are of age. However, even long-term engagements are subject to veto by male family members.

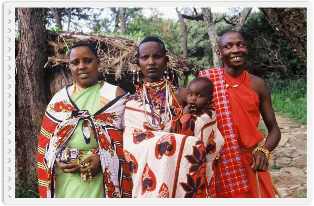

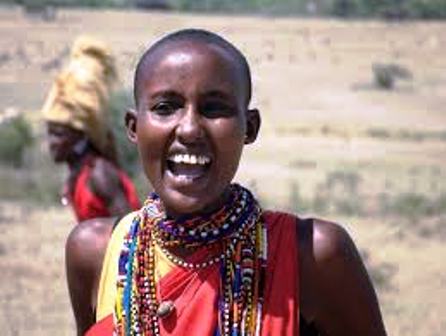

Traditional clothing / Dressing gear of the Maasai People in Kenya

Maasai clothing varies by age, sex, and place. Traditionally, shepherds wore capes made from calf hides, and women wore capes of sheepskin. The Maasai decorated these capes with glass beads. In the 1960s, the Maasai began to replace animal-skin with commercial cotton cloth.

Women tied lengths of this cloth around their shoulders as capes (shuka) or around the waist as a skirt. The Maasai color of preference is red, although black, blue, striped, and checkered cloth are also worn, as are multicolored African designs.

Elderly women still prefer red and dye their own cloth with ochre (a natural pigment). Until recently, men and women wore sandals made from cowhides; nowadays sandals and shoes are generally made of tire strips or plastic.

Young women and girls, and especially young warriors, spend much time on their appearance. Styles vary by age group. The Maasai excel in designing jewelry. They decorate their bodies with tattooing, head shaving, and hair styling with ochre and sheep's fat, which they also smear on their bodies.

A variety of colors are used to create body art. Women and girls wear elaborate bib-like bead necklaces, as well as headbands and earrings, which are colorful and intricate. When ivory was plentiful, warriors wore ivory bands on their upper arms much like the ancient Egyptians. Jewelry plays an important role in courtship.

Traditional Food of the Maasai People

The Maasai depend on cattle for both food and cooking utensils (as well as for shelter and clothing). Cattle ribs make stirring sticks, spatulas, and spoons. Horns are used as butter dishes and large horns as cups for drinking mead.

The traditional Maasai diet consists of six basic foods: meat, blood, milk, fat, honey, and tree bark. Wild game (except the eland), chicken, fish, and salt are forbidden. Allowable meats include roasted and boiled beef, goat, and mutton.

Both fresh and curdled milk are drunk, and animal blood is drunk at special times—after giving birth, after circumcision and excision, or while recovering from an accident. It may be tapped warm from the throat of a cow, or drunk in coagulated form.

It can also be mixed with fresh or soured milk, or drunk with therapeutic bark soups (motori). It is from blood that the Maasai obtain salt, a necessary ingredient in the human diet. People of delicate health and babies eat liquid sheep's fat to gain strength.

Honey is obtained from the Torrobo tribe and is a prime ingredient in mead, a fermented beverage that only elders may drink. In recent times, fermented maize (corn) with millet yeast or a mixture of fermented sugar and baking powder have become the primary ingredients of mead.

The Maasai generally eat two meals a day, in the morning and at night. They have a dietary prohibition against mixing milk and meat.

They drink milk for ten days—as much as they want—and then eat meat and bark soup for several days in between. Some exceptions to this regimen exist. Children and old people may eat cornmeal or rice porridge and drink tea with sugar.

For warriors, however, the sole source of true nourishment is cattle. They consume meat in their forest hideaways (olpul), usually near a shady stream far from the observation of women. Their preferred meal is a mixture of meat, blood, and fat (munono), which is thought to give great strength.

Many taboos (prohibitions) govern Maasai eating habits. Men must not eat meat that has been in contact with women or that has been handled by an uncircumcised boy after it has been cooked.

Traditional education among the Maasai People in Kenya

There is a wide gap between Western schooling and Maasai traditional education, by which children and young adults learned to overcome fear, endure pain, and assume adult tasks. For example, despite the dangers of predators, snakes, and elephants, boys would traditionally herd cattle alone.

If they encountered a buffalo or lion, they were supposed to call for help. However, they sometimes reached the pinnacle of honor by killing lions on their own. Following such a display of courage, they became models for other boys, and their heroics were likely to become immortalized in the songs of the women and girls.

Over the years, school participation gradually increased among the Maasai, but there were few practical rewards for formal education and therefore little reason to send a child to school.

Formal schooling was primarily of use to those involved in religion, agriculture, or politics. Since independence, as the traditional livelihood of the Maasai has become less secure, school participation rates have climbed dramatically.

Cultural Heritage among the Maasai People

The Maasai have a rich collection of oral literature that includes myths, legends, folktales, riddles, and proverbs. These are passed down through the generations.

The Maasai also compose many songs. Women are seldom at a loss for melodies and words when some heroic action by a warrior inspires praise. They also improvise teasing songs, work songs for milking and for plastering roofs, and songs with which to ask their traditional god (Enkai) for rain and other needs.

Traditional Jobs and Employment among the Maasai People

Labor among traditional herding Maasai is clearly divided. The man's responsibility is his cattle. He must protect them and find them the best possible pasture land and watering holes. Women raise children, maintain the home, cook, and do the milking.

They also take care of calves and clean, sterilize, and decorate calabashes (gourds). It is the women's special right to offer milk to the men and to visitors.

Children help parents with their tasks. A boy begins herding at the age of four by looking after lambs and young calves, and by the time he is twelve, he may be able to care for cows and bulls as well as move sheep and cattle to new pastures. Girls help their mothers with domestic chores such as drawing water, gathering firewood, and patching roofs.

Traditional Sports among the Maasai People

While Maasai may take part in soccer, volleyball, and basketball in school or other settings, their own culture has little that resembles Western organized sports.

Young children find time to join in games such as playing tag, but adults find little time for sports or play. Activities such as warding off enemies and killing lions are considered sport enough in their own right.

Recreation among the Maasai People

Ceremonies such as the eunoto , when warriors return to their villages as mature men, offer occasions for parties and merriment. Ordinarily, however, recreation is much more subdued. After the men return to their camp from a day's herding, they typically tell stories of their exploits. Young girls sing and dance for the men. In the villages, elders enjoy inviting their age-mates to their houses or to rustic pubs (muratina manyatta) for a drink.

CRAFTS AND HOBBIES

The Maasai make decorative beaded jewelry including necklaces, earrings, headbands, and wrist and ankle bracelets. These are always fashionable, though styles change as age-groups invent new designs.

It is possible to identify the year a given piece was made by its age-group design. Maasai also excel in wood carvings, and they increasingly produce art for tourists as a supplemental source of income.

SOCIAL PROBLEMS

The greatest challenge the Maasai face concerns adaptation to rapid economic and social change. Increasing encroachment on Maasai lands threatens their traditional way of life.

In the next decade, Maasai will need to address integration into the mainstream modern economies and political systems of Kenyan and Tanzanian society.

The Maasai may fear losing their children to Western schooling, but a modern education has increasingly become a necessity for the Maasai in order to remain competitive with their neighbors and survive.

Shelter

As a historically nomadic and then semi-nomadic people, the Maasai have traditionally relied on local, readily available materials and indigenoustechnology to construct their housing. The traditional Maasai house was in the first instance designed for people on the move and was thus very impermanent in nature.

The Inkajijik(houses) are either star-shaped or circular, and are constructed by able-bodied women. The structural framework is formed of timber poles fixed directly into the ground and interwoven with a lattice of smaller branches, which is then plastered with a mix of mud, sticks, grass, cow dung and human urine, and ash.

The cow dung ensures that the roof is water-proof. The enkaj is small, measuring about 3x5 m and standing only 1.5 m high. Within this space, the family cooks, eats, sleeps, socializes, and stores food, fuel, and other household possessions.

Small livestock are also often accommodated within the enkaji.Villages are enclosed in a circular fence (an enkang) built by the men, usually of thornedacacia, a native tree. At night, all cows, goats, and sheep are placed in an enclosure in the centre, safe from wild animals. Music and dance

Maasai music traditionally consists of rhythms provided by a chorus of vocalists singing harmonies while a song leader, or olaranyani, sings the melody. The olaranyani is usually the singer who can best sing that song, although several individuals may lead a song.

The olaranyani begins by singing a line or title (namba) of a song. The group will respond with one unanimous call in acknowledgment, and the olaranyani will sing a verse over the group's rhythmic throat singing.

Each song has its specific namba structure based on call-and-response. Common rhythms are variations of 5/4, 6/4 and 3/4 time signatures. Lyrics follow a typical theme and are often repeated verbatim over time.

Neck movements accompany singing. When breathing out the head is leaned forward. The head is tilted back for an inward breath. Overall the effect is one of polyphonic syncopation.

Women chant lullabies, humming songs, and songs praising their sons.

Nambas, the call-and-response pattern, repetition of nonsense phrases, monophonic melodies repeated phrases following each verse being sung on a descending scale, and singers responding to their own verses are characteristic of singing by females.When many Maasai women gather together, they sing and dance among themselves.

One exception to the vocal nature of Maasai music is the use of the horn of the Greater Kudu to summon morans for the Eunoto ceremony.

Both singing and dancing sometimes occur around manyattas, and involve flirting. Young men will form a line and chant rhythmically, "Oooooh-yah", with a growl and staccato cough along with the thrust and withdrawal of their lower bodies.

Girls stand in front of the men and make the same pelvis lunges while singing a high dying fall of "Oiiiyo..yo" in counterpoint to the men. Although bodies come in close proximity, they do not touch.

Eunoto, the coming of age ceremony of the warrior, can involve ten or more days of singing, dancing and ritual.

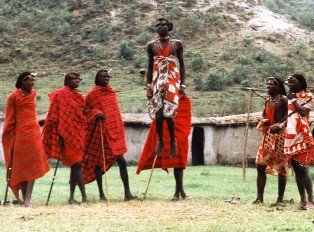

The warriors of the Il-Oodokilani perform a kind of march-past as well as the adumu, or aigus, sometimes referred as "the jumping dance" by non-Maasai. (both adumu and aigus are Maa verbs meaning "to jump" with adumu meaning "To jump up and down in a dance" Warriors are well known for, and often photographed during, this competitive jumping.

A circle is formed by the warriors, and one or two at a time will enter the center to begin jumping while maintaining a narrow posture, never letting their heels touch the ground. Members of the group may raise the pitch of their voices based on the height of the jump.

Body modification

Body modification

Body modificationThe piercing and stretching of earlobes is common among the Maasai. Various materials have been used to both pierce and stretch the lobes, including thorns for piercing, twigs, bundles of twigs, stones, the cross section of elephant tusks and empty film canisters.

Fewer and fewer Maasai, particularly boys, follow this custom.Women wear various forms of beaded ornaments in both the ear lobe, and smaller piercings at the top of the ear.

The removal of deciduous canine tooth buds in early childhood is a practice that has been documented in the Maasai of Kenya and Tanzania.

There exists a strong belief among the Maasai that diarrhoea, vomiting and other febrile illnesses of early childhood are caused by the gingival swelling over the canine region, which is thought to contain 'worms' or 'nylon' teeth.

This belief and practice is not unique to the Maasai. In rural Kenya a group of 95 children aged between six months and two years were examined in 1991/92.

87% were found to have undergone the removal of one or more deciduous canine tooth buds. In an older age group (3–7 years of age), 72% of the 111 children examined exhibited missing mandibular or maxillary deciduous canines.

Hair

Head shaving is common at many rites of passage, representing the fresh start that will be made as one passes from one to another of life's chapters.Warriors are the only members of the Maasai community to wear long hair, which they weave in thinly braided strands.

Upon reaching the age of 3 "moons", the child is named and the head is shaved clean apart from a tuft of hair, which resembles a cock's comb, from the nape of the neck to the forehead.

The cockade symbolizes the "state of grace" accorded to infants.A woman who has miscarried in a previous pregnancy would position the hair at the front or back of the head, depending on whether she had lost a boy or a girl.

Two days before boys are circumcised, their heads are shaved.The young warriors then allow their hair to grow, and spend a great deal of time styling the hair. It is dressed with animal fat and ocher, and parted across the top of the head at ear level.

Hair is then plaited: parted into small sections which are divided into two and twisted, first separately then together. Cotton or wool threads may be used to lengthen hair. The plaited hair may hang loose or be gathered together and bound with leather.When warriors go through the Eunoto, and become elders, their long plaited hair is shaved off.

As males have their heads shaved at the passage from one stage of life to another, a bride to be will have her head shaved, and two rams will be slaughtered in honor of the occasion.

Maasai lion hunting

The Maasai people have traditionally viewed the killing of lions as a rite of passage. Historically, lion hunts were done by individuals, however, due to reduced lion populations, lion hunts done solo are discouraged by elders.

Most hunts are now partaken by groups of 10 warriors. Group hunting, known in Maasai as olamayio, gives the lion population a chance to grow. Maasai customary laws prohibit killing a sick or infirm lion. The killing of lionesses is also prohibited unless provoked.

At the end of each age-set, usually after a decade, the warriors count all of their lion kills to compare them with those hunted by the former age-set in order to measure accomplishment.

Group hunting

Empikas (warrior delegation) plan a lion hunt in advance in secret. Only the warriors are permitted to know about the day of the hunt. The secret is considered so important that Ilbarnot (young warriors) from the same age-set are denied information regarding the hunt, due to the older warriors fearing discovery from anti-hunt groups. If a warrior is found guilty of spreading rumours, he is punished through beating. In addition, the guilty warrior will be looked down upon throughout his entire age group's cycle.

Solo hunting

Solo lion hunting requires confidence and advanced hunting skills, requiring a dedicated warrior. Unlike group hunting, solo lion hunting is usually not an organised event, sometimes occurring when a warrior is out herding cattle.

The journey

The lion hunt starts at dawn, when elders and women are still asleep. The warriors meet discreetly at a nearby landmark where they depart to predetermined areas. Before departing, the Ilmorijo (older warriors) filter out the group in order that only the bravest and strongest warriors take part.

The resulting group is known as Ilmeluaya (fearless warriors). The rejected young warriors are commanded by older warriors to keep the information of the hunt confidential, until the return of their favoured colleagues.

There have been cases whereby older warriors have forced warriors to give up their excess weaponry, seeing as it is considered insulting to bring more than a spear which is sufficient to kill a lion.

After a successful hunt, a one-week celebration takes place throughout the community. The warrior who struck the first blow is courted by the women and receives an Imporro, a doubled-sided beaded shoulder strap. The warrior wears this ornament during ceremonies. The community will honor Olmurani lolowuaru (the hunter) with much respect throughout his lifetime.

Body parts

The Maasai do not eat game meat, and use the bodies of their killed lions for three products; the mane, tail and claws. The mane is beaded by women of the community, and given back to the hunter, who wears it over his head on special occasions.

After the meat ceremony, when a warrior becomes a junior elder, the mane is thrown away and greased with a mixture of sheep oil and ochre. This sacrificial event is done to avoid evil spirits.

The lion's tail is stretched and softened by the warriors, then handed over to the women for beading. The warriors keep the tail in their manyatta (warriors camp), until the end of warriorhood.

The lion tail is considered the most valuable product and after graduation, the warriors must gather to pay their last special respect to the tail before it is disposed of.

Other Pages of Interest

Kenya Art |

Kenya Festivals |

Kenya Gender Issues |

Kenya Gestures |

Kenya Greetings |

Kenya History |

Kenya Language |

Kenya Literature |

Kenya Modern Culture |

Kenya Music |

Kenya National Anthem |

National Dress Cord of Kenya |

Kenya People |

Kenya Respect |

Kenya Taboos |

Kenya Television and Culture |

Recent Articles

-

Garam Masala Appetizers ,How to Make Garam Masala,Kenya Cuisines

Sep 21, 14 03:38 PM

Garam Masala Appetizers are originally Indian food but of recent, many Kenyans use it. Therefore, on this site, we will guide you on how to make it easily. -

The Details of the Baruuli-Banyara People and their Culture in Uganda

Sep 03, 14 12:32 AM

The Baruuli-Banyala are a people of Central Uganda who generally live near the Nile River-Lake Kyoga basin. -

Guide to Nubi People and their Culture in Kenya and Uganda

Sep 03, 14 12:24 AM

The Nubians consist of seven non-Arab Muslim tribes which originated in the Nubia region, an area between Aswan in southern

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.