Turkana people of Kenya and their Culture

Do you need information about Turkana people of Kenya , Do you need to learn about the culture of the Turkana people in Kenya? This is the page to give you detailed information about Turkana tribe and their culture in Kenya.

The Turkana are the second largest group of nomadic pastoralists in Kenya who live in nothern Kenya - numbering over 200,000 they occupy a rectangular area bordered by Lake Turkana in northern Kenya and Ethiopia on the east, Uganda on the west, Sudan on the north.

The Turkana people emerged as a distinct ethnic group sometime during the early to middle decades of the nineteenth century.

Oral history and archaeological evidence suggest that, prior to A.D. 1500, the ancestors of the Ateker Language Group lived somewhere in the southern Sudan and most likely subsisted as hunting and gathering peoples.

After beginning their southern migration, these ancestral peoples incorporated both agricultural and pastoral pursuits, and eventually split into groups that emphasized one subsistence strategy or the other.

The period from 1500 to 1800 appears to have been characterized by frequent splitting and fusing of ethnic groups, and shifting alliances among the groups. During this time, the Karamojong established a distinct identity with a subsistence system based on the raising of livestock, principally cattle, combined with small-scale agriculture.

Oral histories suggest that the Jie seceded from the Karamojong, and that a group split off from the Jie and established themselves in the region near the headwaters of the Tarach River, in what is now Turkana District, sometime during the early part of the eighteenth century.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, Turkana cattle camps began to push down the Tarach in search of new pastures upon which to graze their animals.

As they moved westward, the Turkana encountered other pastoral groups, some of which herded camels (most likely the Rendille and Borana). As the Turkana expanded eastward, they began both to assimilate and disperse other groups.

They first pushed to the north and east to Lake Turkana, and then to the south, crossing the Turkwell River. It appears that by 1850 the Turkana occupied much of the territory they use today.

The first European to enter into the land of the Turkana was Count Samuel Teleki von Szek, whose expedition reached Turkana in June of 1888. He was preceded by Swahili caravans in search of ivory, which first arrived in 1884.

About the same time that the Swahili arrived in the south of Turkanaland, Ethiopian ivory hunters began arriving in the north.

Within a few years, there ensued a period of conflict and contestation between the British and the Ethiopians over the colonial domination of the Turkana, which lasted until 1918.

The Turkana resisted British domination of their homeland throughout the early part of the twentieth century.

Turkana raiding on their pastoral neighbors, especially against the Pokot to the south, caused large-scale social disruption and influenced the British decision to launch one of the largest military expeditions they ever mounted against an indigenous people.

In 1918 a combined force of over 5,000 well-armed men, consisting of Sudanese troops, troops of the Kings African Rifles, and levies composed of warriors from groups antagonistic to the Turkana, launched what came to be known as the Labur Patrol.

The Labur Patrol broke the military might of the Turkana; in 1926 civil administration was reintroduced, and in 1928 taxes were reinstated. The period from 1929 until World War II appears to have been peaceful.

Beginning in the 1950s, the Turkana again began to resist British domination, and the British launched a series of military expeditions against the Turkana. The use of occasional military forays against the Turkana was continued by the Kenyan government following independence in 1963.

Development in Turkana District was slow. Only two primary schools operated in the district at the time of independence.

During the 1970s major efforts were made to help the Turkana integrate into the larger Kenyan economy; however, antagonistic relations among the Turkana and their neighbors continued, and by the early 1980s the entire district was considered highly insecure.

Insecurity combined with two severe droughts in the early 1980s to inhibit development efforts. Despite the growth of settlements, the area remains remote, insecure, and relatively underdeveloped.

History of Turkana People in Kenya

The Turkana entered Turkana basin from the north as one unit of the Ateker confederation.

The Ateker cluster split as a result of internal differences leading to emergence of distinct independent groups. Turkana people emerged as a victorious group.

The victory of the Turkana people in the initial Ateker conflict led to enmity between Turkana people and other Ateker cluster groups. Ateker cluster groups formed military alliances against The Turkana.

The Turkana emerged victorious again by co-opting young people from conquered groups. The military power and wealth of the Turkana increased in what is now the northern plains of Turkana.

The establishment of the Turkana people developed as a distinct group which expanded southwards conquering ethnic nations south of its borders.

The Turkana people easily conquered groups it came in contact with by employing superior tactics of war, better weapons and military organization. By 1600s, the Turkana basin had been fully occupied by Turkana people and allied friendly groups.

There was a relative long period of peace among indigenous ethnic communities around Turkana until the onset of European colonization of Africa.

Sporadic conflicts involved Turkana fights against Arab, swahili and Abyssinian slave raiders and ivory traders. European colonization brought a new dimension to conflict with Turkana putting up a lasting resistance to a complex enemy, the British.

The Turkana put up and maintained active resistance to British colonial advances leading to a passive presence of colonial administration. By the outbreak of WW I, few parts of Turkana had been put under colonial administration.

From WW I through to end of WW II, Turkana actively participated in the wars as allies of Britain against invading Italy. Turkana was used as the launching pad for the war against invading Italian forces leading to the liberation of Abyssinia.

After WW II, the British led disarmament and pacification campaigns in Turkana, leading to massive disruptions and dispossession of Turkana pastoralists.

The colonial administration practiced a policy of deliberate segregation of Turkana people by categorizing Turkana Province as a closed district. This led to marginalization and underdevelopment in the lead up to Kenya's independence.

Clothing of Turkana People in Kenya

Traditionally, men and women both wear wraps made of rectangular woven materials and animal skins. Today these cloths are normally purchased, having been manufactured in Nairobi or elsewhere in Kenya.

Often men wear their wraps similar to tunics, with one end connected with the other end over the right shoulder, and carry wrist knives made of steel and goat hide. Men also carry stools (known as ekicholong) and will use these for simple chairs rather than sitting on the hot midday sand.

These stools also double as headrests, keeping one's head elevated from the sand, and protecting any ceremonial head decorations from being damaged.

It is also not uncommon for men to carry several staves; one is used for walking and balance when carrying loads; the other, usually slimmer and longer, is used to prod livestock during herding activities.

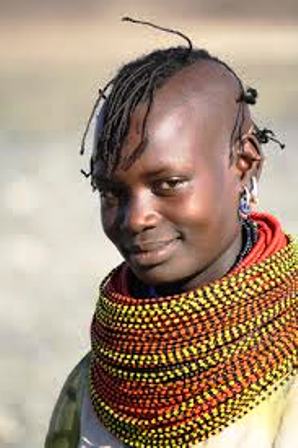

Women will customarily wear necklaces, and will shave their hair completely which often has beads attached to the loose ends of hair. Men wear their hair shaved.

Women wear two pieces of cloth, one being wrapped around the waist while the other covers the top. Traditionally leather wraps covered with ostrich egg shell beads were the norm for women's undergarments, though these are now uncommon in many areas.

The Turkana people have elaborate clothing and adornment styles. Clothing is used to distinguish between age groups, development stages, occasions and status of individuals or groups in the Turkana community.

Today, many Turkana have adopted western-style clothing. This is especially prominent among both men and women who live in town centers throughout Turkana.

Livestock of Turkana People in Kenya

The Turkana rely on several rivers, such as the Turkwel River and Kerio River. When these rivers flood, new sediment and water extend onto the river plain that is cultivated after heavy rainstorms, which occur infrequently. When the rivers dry up, open-pit wells are dug in the riverbed which are used for watering livestock and human consumption. There are few, if any, developed wells for community and livestock drinking water, and often families must travel several hours searching for water for their livestock and themselves.

Livestock is an important aspect of Turkana culture. Goats, camels, donkeys and zebu are the primary herd stock utilized by the Turkana people. In this society, livestock functions not only as a milk and meat producer, but as form of currency used for bride-price negotiations and dowries. Often, a young man will be given a single goat with which to start a herd, and he will accumulate more via animal husbandry. In turn, once he has accumulated sufficient livestock, these animals will be used to negotiate for wives. It is not uncommon for Turkana men to lead polygynous lifestyles, since livestock wealth will determine the number of wives each can negotiate for and support.

Food of Turkana People in Kenya

Turkana rely on their animals for milk, meat and blood. Wild fruits are gathered by women from the bushes and cooked for 12 hours. Slaughtered goats are roasted on a fire and only their entrails and skin removed. Roasting meat is a favorite way of consuming meat.

The Turkana often trade with the Pokots for maize and beans, Marakwet for Tobacco and Maasai for maize and vegetables. The Turkana buy tea from the towns and make milk tea. In the morning people eat maize porridge with milk, while for lunch and dinner they eat plain maize porridge with a stew.

Zebu are only eaten during festivals while goat is consumed more frequently. Fish is taboo for some of the Turkana clans (or brands, "ngimacharin"). Men often go hunting to catch dik dik, wildebeest, wild pig, antelope, marsh deer, hare and many more. After the hunt men go out again to gather honey which is the only sweet thing the Turkana have.

Houses of Turkana People in Kenya

Houses are constructed over a wooden framework of domed saplings on which fronds of the Doum Palm tree Hyphaene thebaica, hides or skins, are thatched and lashed on.

The house is large enough to house a family of six. Usually during the wet season they are elongated and covered with cowdung. Animals are kept in a brush wood pen. Due to changes in the climatic conditions most Turkana have started changing from the traditional method of herding cattle to agro-pastoralism.

Turkana Traditional Religion

A clear boundary is not drawn between the sacred and the profane in Turkana society. In this regard, Turkana traditional religion is undifferentiated from Turkana social structure or epistemological reality—the religion and the culture are one.

The Turkana are pastoralists whose lives are shaped by the extreme climate in which they live. Each day one must seek to find the blessings of life—water, food, livestock, wives, children—in a manner that appeases the ancestral spirits and is in harmony with the peace within the community.

Properly following the traditions (ngitalio) in daily life will certainly lead to blessing. Blessings are understood to be an increase in wealth, whether livestock, children, wives or even food.

It is only through proper relationships with God (Akuj) and the ancestors, proper protection from evil, and participation in the moral economy of the community that one can be blessed.

Essentially, Turkana believe in the reality of a Supreme Being named Akuj. Not much is known about Akuj other than the fact that he alone created the world and is in control of the blessings of life.

There is also a belief in the existence of ancestors, ngipean or ngikaram, yet these are seen to be malevolent, requiring animal sacrifices to be appeased when angry. When angered or troubled, the ancestors will possess people in the family in order to verbally communicate with their family.

There is also the recognition of “The Ancestor,” Ekipe, who is seen as much more active in the everyday lives of people, yet only in negative ways.

There is much concern over protecting one’s family and oneself from the evil of the Ekipe. Turkana Christians and missionaries equate ekipe with the biblical character of Devil or Satan and this has shifted more traditional understandings of ekipe away from “an evil spirit” to “The Evil one.” Turkana religious specialists, ngimurok, continue to act as intermediaries between living people and ancestors and also help in problem solving in communities.

As in most African traditional religions, traditional religious specialists in Turkana are present and play an active role in almost every community event.

Ngimurok help to identify both the source of evil, sickness or other problems that present themselves, and the solution or specific cure or sacrifice that needs to take place in order to restore abundant life in the family and the community.

There are various types of diviners differentiated by the emuron’s source of revelation. According to Barrett, the “true diviners,” also known as the “diviners of God,” are the most respected of the ngimurok because they receive revelations directly from Akuj, normally through dreams,.

These “true diviners” follow in the pattern of the most famous Turkana ngimurok, Lokerio and Lokorijem.

the land scape to tukana land

the land scape to tukana landThe latter regularly received dreams from Akuj informing him of the location of the British Army during early 20th century colonial struggles, and the former is said to have used the power and knowledge of God to divide Lake Turkana so that warriors could walk across the lake to steal camels]

These ngimurok of God can still be found throughout Turkana, each in their own territory, alongside specialized ngimurok who have received specific abilities to read tea leaves, tobacco, intestines, shoes, stones and string.

There are also hidden evil specialists, ngikasubak, who use objects in secret to work against people in the community, and ngikapilak, who specialize in pronouncing very strong curses employing the use of body parts from those recently deceased, but these are not included in the term emuron.

Ngimurok are the people that Akuj and the Fathers speaks to in dreams; they are also the ones who can communicate with the ancestors to discern what sort of animal sacrifice is needed to restore peace, bring rain, find a remedy for a child’s illness, or who can properly bless the families at a wedding.

The ngimurok in each area receive direct revelations from Akuj, who is still directly active and concerned with the creation.

These ngimurok do not speak or receive messages through an intermediary god or spirit through possession. While ancestor possessions are common in Turkana, they normally occur among younger people at the home, so that the ancestor can communicate their message to those in the home.

The emuron would then be consulted as to what should be done. Ngimurok are not known as people who are normally possessed. Apart from the ngimurok, there are also important clan rituals in Turkana that represent the acknowledgement and transitions of life force.

The most important rituals are the birth rituals (akidoun), male and female initiation rituals that do not include circumcision (asapan and akinyonyo), marriage rituals (Akuuta), annual blessing sacrifices (Apiaret a awi), and death rituals (Akinuuk).

live stock of the turkana

live stock of the turkanaEach of these rituals is overseen by the elders of the clan, both men and women. The elders also over see the community wide wedding rituals, but an emuron normally plays a role in blessing the marriage.

Traditional dress and ornaments is of vital importance, much emphasis being placed on adornment of both women and young Moranis (warriors) .

Their neck is hidden by brightly colored beads, any object, even the most simple and ordinary in western eye is greatly sought after as an ornament to increase there charm.

Located primarily in northwest Kenya and around Lake Turkana, the Turkana people of Kenya migrated to the area from the west.

According to legend, young men of the Jie tribe went into the Tarash valley in search of an ox that they had lost. While there they met an old Jie woman gathering fruit.

Impressed with the area, they talked other young people into joining them and moved with their stock. Since that time, the Turkana and Jie have been allies.

The Turkana are divided into the forest people (Nimonia) and the people of the plains (Nocuro). The roughly twenty clans (ategerin) do not form the basis for everyday Turkana society, as they do in many tribes.

community of the turkana

community of the turkanaTurkana communities are based instead on the neighborhood (adakar). Turkana men are divided into two age-sets, which are the Stones (Nimur) and the Leopards (Nerisai).

As with the Maasai and Samburu, milk mixed with blood is the main food of the Turkana. Cattle are important for a variety of reasons, with hides providing sleeping mats and material for sandals. Camels are important, as are the sheep and goats herded by the children and used for meat.

Donkeys are also present, although used only as pack animals. Dried milk (edodo) is made by boiling fresh milk and allowing it to dry on skins.

Easily digestible camel milk is valuable as baby food. Dried meal is made with crushed berries, which are also mixed with blood and made into cakes.

The Turkana people of Kenya generally live in extended family settings, and the family awi often involves two enclosures. One is the awi napolon, which is the main enclosure where the head of the family lives.

The other is the awi abor, where the additional wives and their children, as well as married sons, live. The homestead's main entrance faces east, with the chief wife's day hut (ekal) and night hut (akai) on the right.

Turkana families often build next to the awi of other families, creating the neighborhoods that are the Turkana's effective communities.

Turkana marriages take place over a three year period. Marriage is not complete until the first child has reached walking age. The purpose of this extended time is to ensure the ritual, spiritual, and social wellbeing of those involved.

The bride price (paid by the bridegroom) usually involves quite a few cattle or camels, which come from the herds of the suitor, his father, his father's and mother's brothers, stock associates, and bond-friends. The wife occupies an important position in the awi, and maintains close ties with both her husband and her father and brothers.

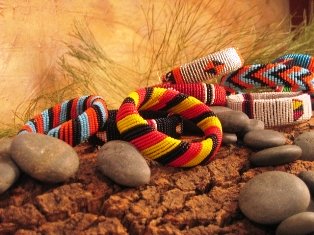

Turkana women often wear huge quantities of beads around their necks, along with an aluminum or brass neck ring (alagam).

The traditional Turkana weapons, used to protect their herds and possessions from wild animals and other tribes, include an eight foot long spear, a knobkerrie fighting stick, wrist knives, fingerhooks, and a shield made from buffalo, giraffe, or hippo hide.

The Turkana people of Kenya are skilled at carving wooden water troughs and containers. Other containers are made from hides and decorated with beadwork

Other Pages of Interest

Kenya Culture | Akamba | British Colonialists | Crafts | Cultural Business Meetings | Cultural Communication | Cultural Eye Contact | Cultural Gestures | Gift Giving | Cultural Law | Cultural Music | Cultural Space | Cultural Time | How to Talk in Kenya |

Recent Articles

-

Garam Masala Appetizers ,How to Make Garam Masala,Kenya Cuisines

Sep 21, 14 03:38 PM

Garam Masala Appetizers are originally Indian food but of recent, many Kenyans use it. Therefore, on this site, we will guide you on how to make it easily. -

The Details of the Baruuli-Banyara People and their Culture in Uganda

Sep 03, 14 12:32 AM

The Baruuli-Banyala are a people of Central Uganda who generally live near the Nile River-Lake Kyoga basin. -

Guide to Nubi People and their Culture in Kenya and Uganda

Sep 03, 14 12:24 AM

The Nubians consist of seven non-Arab Muslim tribes which originated in the Nubia region, an area between Aswan in southern

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.